Apple vs. Everyone

Polymatter is a popular YouTube creator who has spent the past decade crafting educational and analytical videos. Their chosen topics of business, technology and geopolitics, combined with slick motion graphics, have proved successful, racking up hundreds of millions of views and about 2 million subscribers to date. I’ve watched their videos for years and always found them engaging, admiring Polymatter’s ability to break down complex subjects into accessible narratives, and I’d say the channel is a respected staple of the educational YouTube community.

However, Polymatter’s recent video concerning Apple has not received the usual response, with a dislike rate nearing 50%. It's about the antitrust lawsuit filed by the US government against Apple Inc., and many viewers seem to think that Polymatter makes bad faith arguments in this video, leaves out important context, and overall comes across as having a strong bias in Apple’s favour. Some even accuse Polymatter of taking money from Apple on the sly, which I think is insane – but I do think there’s much more to the story of this lawsuit than what Polymatter chooses to tell, which is why I’ve made this video.

Today we’re going to look at the complaint put forward by the US government against Apple, and see how Polymatter’s video holds up under closer examination. And in the interest of not being a total hypocrite, let me be clear about one thing: I largely agree with the points put forward by the US government. In other words, if Polymatter’s video is biased, then my video certainly is. My intent is not to present both sides of the argument with equal credence and weight, but rather to turn the legal jargon of the complaint into something more digestible, and to create a counter-balance to the allegedly biased presentation in the Polymatter video. I will also make my own assessment about whether the Polymatter video actually is biased or not so keep reading for that tasty drama.

But to have a chance of understanding this at all, we’re going to have to start with a history lesson.

1. Playing Fair: A History Lesson

Apple in the 1990s was a struggling company in the personal computer market where there was one dominant player: Microsoft. Apple had been first to create an operating system with a graphical user interface but by the mid-1980s, Microsoft had followed suit – or as Apple would say, Microsoft had copied them. Bill Gates set the aim that “only applications that take advantage of Windows [should] be competitive in the long run” and by the 90s, their operating system was gaining traction while Apple fell behind, preoccupied with a bloated and confusing product line. I know you’ve heard of the iPad, but have you heard of the Newton MessagePad? How about the Pippin?

By 1997, Apple was reporting losses of hundreds of millions of dollars – per quarter – and though Apple and Microsoft struck a deal that helped turn things around, Steve Jobs still criticised Microsoft for dirty monopoly tactics and Apple went to the Department of Justice in hopes of getting Microsoft “to play fair.” Microsoft, meanwhile, was doing very well, with their Windows 95 taking great strides in OS design and taking the market by storm.

Microsoft had one threat looming on the horizon, but it wasn’t Apple — it was Netscape.

Before most people had access to the internet, what mattered was what YOUR computer could do. The hardware and software you owned shaped your digital experience, which, given Windows’ dominant position, meant that Microsoft shaped your experience. But in the 1990s, the Internet was becoming a mainstream platform for communication and commerce; it was a new way to use your computer and it was outside of Microsoft’s control. The most popular browser was created by Netscape, a small company founded in 1994 which quickly grew an enormous valuation. This did not sit right with Microsoft, who used their dominant position to insert their own web browser as the default on all Windows devices.

If you’ve ever used Internet Explorer, this should piss you off.

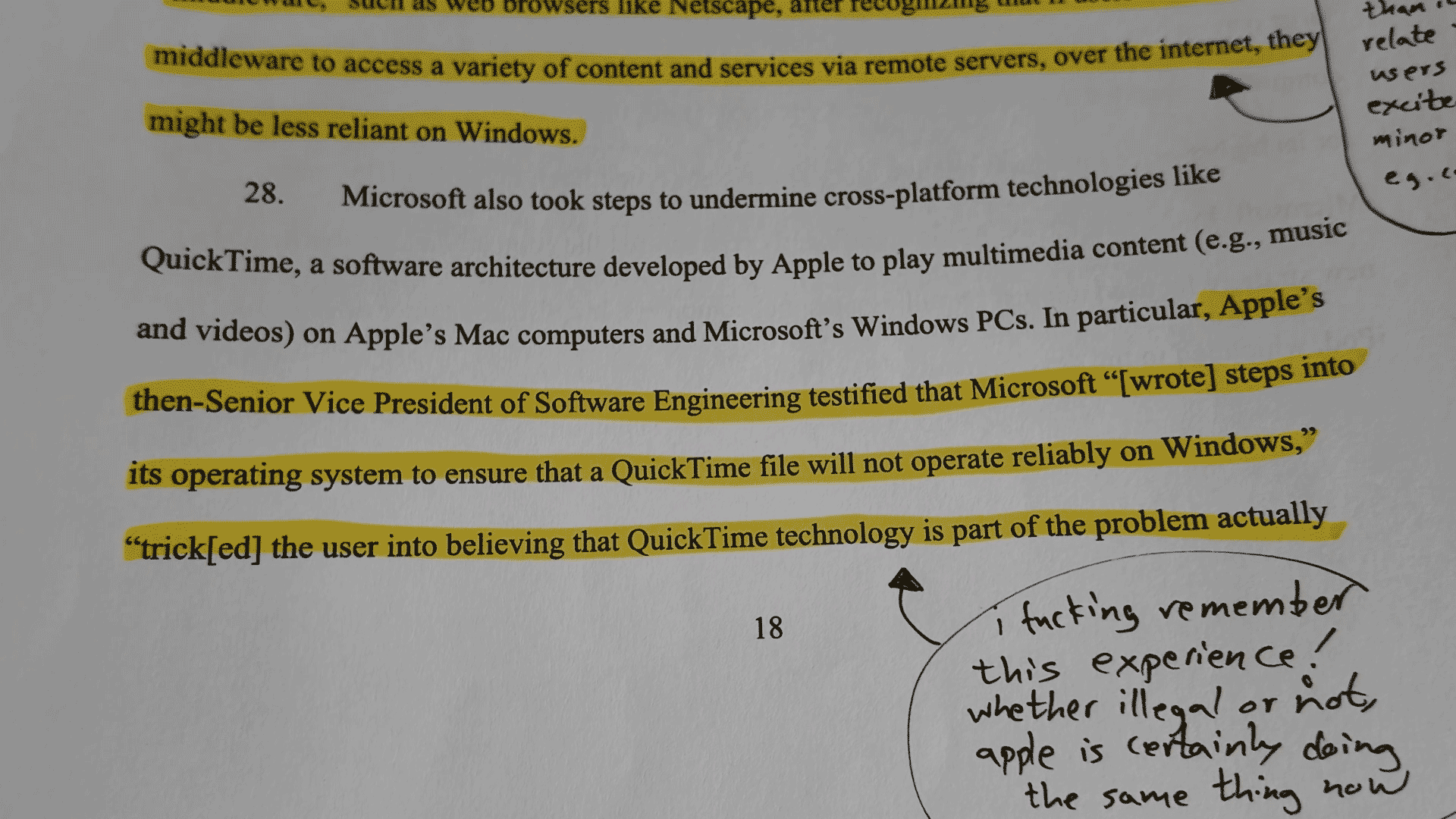

In 1998, the US Department of Justice filed an antitrust lawsuit against Microsoft, alleging that the company had abused its monopoly power to stifle competition, maintaining its dominance at the expense of innovation and the choice of consumers. One of the witnesses who testified was Apple’s Senior Vice President of Software Engineering who said that Microsoft “[had written] steps into its operating system to ensure that a QuickTime file [Apple’s video format] will not operate reliably on Windows,” thereby “trick[ing] the user into believing that QuickTime technology is part of the problem actually caused by the Windows operating system.”

The court found Microsoft guilty and ordered the company to be broken up into two separate entities, which, as you may have noticed, didn’t happen. Microsoft appealed and reached a settlement agreement under which they had to be more open about allowing other software on their OS, specifically sharing access to their application programming interfaces (or APIs) with third-party companies.

Apple meanwhile was starting to do OK; they got some momentum with the release of the iMac in 98, but they wouldn’t catch lightning in a bottle until the release of the first iPod. Actually, the first iPod sold fine but it wasn’t a smash hit, in part because it was only compatible with Mac computers. It was the second generation iPod that introduced Windows compatibility, allowing this new MP3-player to be adopted outside Apple’s existing user base, and it was from there that things really took off for Apple, later leading to the iPhone.

Would the iPod’s Windows compatibility have been possible without the settlement agreement between the Department of Justice and Microsoft? Probably, but you can be sure that with the DOJ breathing down their neck, Microsoft wasn’t going to intentionally suffocate the Windows version of iTunes, the way they’d tried to do to QuickTime and Netscape. And note that though Windows was the dominant OS, Microsoft wasn’t taking a 30% cut of every song you bought on the Windows version of iTunes.

Why did Microsoft make these questionable decisions? Why was Netscape such a threat? Well, web browsers were platform-independent, a type of “middleware” that made users less reliant on the operating system that was Microsoft’s cash cow. If software and services moved to the web, the underlying operating system and hardware didn’t matter as much, and users wouldn’t be as tied to the Windows ecosystem.

You can probably see where I’m going with this, right?

Web browsers made devices more interoperable, and interoperability, I would argue, is empirically a good thing for consumers, no matter how bad it might be for monopolistic tech giants interested in exponential profit growth.

I want you to remember what Apple had to say about Microsoft intentionally breaking Quicktime and making it worse on the Windows platform. Because they are doing exactly the same thing to competitors and independent developers today!

2. Cloud Rent: The Apple Tax

Before we get into Fitbits and Green Bubbles, let’s clarify what’s actually being alleged. Apple has a goal of locking users into their ecosystem – and creating a great ecosystem of hardware and software that makes people want to stick around is not illegal. The question, rather, is whether they’ve used their dominant position to screw people over.

In their video, Polymatter spends a lot of time on what Apple customers think of Apple products, and the DOJ does allege that Apple’s goal of stifling competitors leads to it making its own products worse, but the complaint focuses on “Apple’s use of its dominance to impose contracts and rules that restrict the behaviour and design decisions of companies other than Apple.”

So what contracts and rules are they talking about?

Well, the iPhone that launched in 2007 had limited functionality compared to what we’re used to today. There were no third-party apps, just the ones made by the company. But within a year, Apple had launched their App Store with 500 applications from independent developers – a number that has since grown into the millions. Because this was such a new type of technology, there were no regulations forcing Apple to open up its new platform and allow developers in, but they chose to do so – and it was a good choice, both for consumers and for Apple. Without having to do the hard work of programming themselves, they had turned their phone with an iPod into a device that could do seemingly anything!

But the lack of regulation meant that there was no oversight for how Apple wielded their newfound power. Whenever a new innovative app came into being – through someone else’s hard work – Apple didn’t just benefit from the increased value brought to the iPhone, they also took a 30% cut of the sales price of the app. And if you made any purchases in that app or started any subscriptions, Apple took a cut of that as well.

This is why you can’t start a Spotify subscription in their app – Spotify doesn’t want to give away 30% of its revenue. And who could blame them? What exactly are developers getting for that 30%? For years, Apple told them they were paying for promotion in the app, but then they started charging additional fees for promotion – and if you don’t pay up, your competitor probably will and, don’t worry, we’ll put them right at the top when someone is searching for your app. But hey, at least Apple got another 4.4 billion dollars for these new ads (in 2022).

What you’re actually paying is what the DOJ calls a “monopoly rent”, meaning one set without competition and unrelated to the actual cost of the service provided by Apple. This “Apple tax”, as some call it, is one of the three main ways that Apple illegally exploits its monopoly, according to the DOJ, and it doesn’t come up at all in the Polymatter video.

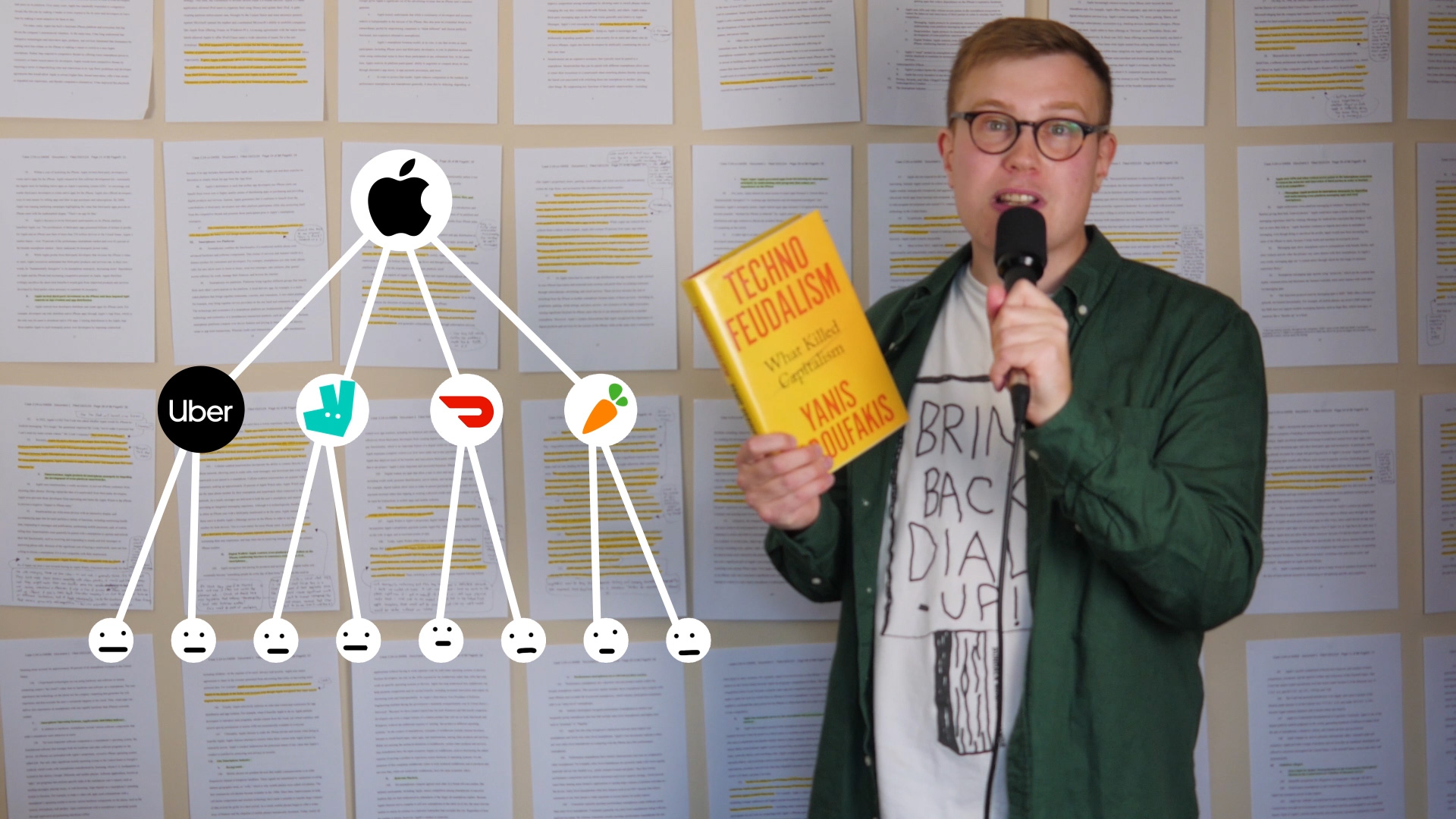

In his book Technofeudalism, Yanis Varoufakis calls this “cloud rent” and describes the App Store as the first “cloud fief”. In a feudal system, all the land belongs to the monarch who grants lords custody of parcels of land, with the responsibility of extracting value from that land and the associated peasantry, all while paying taxes back to the top. Varoufakis’ thesis is that capitalism is dead and we’re back in that system, with cloudalist monarchs like Apple and Amazon exploiting the lords beneath them who in turn exploit the peasantry — meaning us. He describes how:

![Companies like Uber, Lyft, Grubhub, DoorDash […] wired into their cloud fiefs a vast array of drivers, delivery people, cleaners, restauranteurs — even dog walkers — collecting from these unwaged, piece-rate workers a fixed cut of their earnings, too. A cloud rent. - Technofeudalism, Yanis Varoufaki Companies like Uber, Lyft, Grubhub, DoorDash […] wired into their cloud fiefs a vast array of drivers, delivery people, cleaners, restauranteurs — even dog walkers — collecting from these unwaged, piece-rate workers a fixed cut of their earnings, too. A cloud rent. - Technofeudalism, Yanis Varoufaki](https://awesomepedia.org/video/apple-vs-everyone/images/technofeudalism-quotes.jpg)

Varoufakis claims Amazon and the App Store aren’t marketplaces because monopolies have long since been established, and companies like Nokia, Sony and Blackberry never built their own app stores was that it was too late — with Apple quickly cornering the market, third-party developers couldn’t waste resources developing for platforms with fewer users — especially not while giving up 30% of their profits to their overlord.

Now, if only there was a way that apps could work across platforms!

3. Super Apps & Cloud Streaming: Barbarians at the Gates

The second way that Apple illegally exploits their monopoly — according to the DOJ — is that they use their control over app distribution to enforce “rules and contractual restrictions that stop or delay developers from innovating in ways that threaten Apple’s power.” Two examples of this are the restrictions they’ve imposed on so-called Super Apps and Cloud Streaming. Though these are different technologies, both are a type of “middleware” that open new possibilities for users and thereby threaten Apple in the same way that web browsers like Netscape threatened Microsoft in the 1990s. They weaken the user’s dependence on the Apple ecosystem, Super Apps on the software side, and Cloud Streaming on the hardware side.

A “super app” is one that can serve as a platform for many smaller apps, but it’s not the same as just putting a bunch of apps in a folder. Unlike apps from the App Store, these smaller programs can be created using cross-platform languages like HTML5 and JavaScript, meaning that you only need to create one version of each and it would run just fine on any operating system or browser. So besides making it easier for consumers to switch phones, the versatility of super apps could be a real boon to developers looking to tap into economies of scale across both iOS and Android. But it won’t surprise you to learn that Apple only wants you to program using their approved programming languages and hardware, meaning that your work can’t be easily ported elsewhere.

The complaint quotes one Apple manager who stated that allowing super apps to become “the main gateway where people play games, book a car, make payments, etc.” would “let the barbarians in at the gate.” (p. 30)

While there’s no “official” ban on super apps, Apple has a habit of imposing restrictions that make it practically impossible to do what they don’t want you to. For example, they’ve blocked mini programs from using Apple’s payment system (even if you wanted to pay the 30% Apple tax) and they’ve banned super apps from using icons or graphics to display their mini programs. In practice, this means that there are no real super apps available to US customers.

The main example of a super app that people bring up, and the one described as a nightmare scenario by Polymatter, is China’s WeChat. Polymatter says:

”the DOJ is right, super apps are bad for apple [the DOJs] mistake is assuming that super apps must be good for users […] Super apps merely replace one monopolist with another […] Would you want all 10-20-100 of the apps on your phone squeezed into one? For most people this would simply add an additional layer of complexity […] In the world the DOJ imagines, one super app reigns supreme across all platforms […] Restricting superapps is good for users”

I really think it’s weird that Polymatter tries to make it seem like the DOJ would force you to use super apps? And, just so you know, all these proclamations are set to very ominous music.”

The internet is designed differently for different cultures — just look at any Japanese website. I don’t personally see the appeal of super apps designed for Asian markets. I prefer software designed to do one thing well, unlike what, say, Instagram and TikTok have become. But due to Apple’s restrictions, we have not seen what a proper “designed for Americans” super app would look like. And that is entirely the DOJs point. I’m not a huge fan of this whole capitalism thing, but surely if you are, you can see how the “free market” is restrained here?

In the same way that Super Apps could make easier to switch from Apple software, cloud streaming could reduce people’s reliance on Apple hardware. Given where internet speeds and cloud computing is at, there’s no need to carry around expensive, high performance computers in our pockets. Whether you want to play games, edit video or just work, we’re at a point where the computing can happen remotely. As one Apple manager is quoted in the complaint:

“Imagine buying a [expletive] Android for 25 bux at a garage sale and it works fine . . . . And you have a solid cloud computing device. Imagine how many cases like that there are.”

Yes, indeed, imagine. But what’s good for consumers here is bad for Apple (even Polymatter agrees on this one) so Apple has done the same thing they did to super apps. While there may be no explicit ban they’ve complicated their rules and app moderation to choke out this whole field of apps before it could ever bloom.

Polymatter says that Super Apps would be bad for consumers and cloud streaming would be good. But even if you’re solely focused on “what’s better for consumers”, which is a deeply flawed way of approaching antitrust, please consider that both types of technology could increase competition and thereby force Apple to lower their prices. Which the company would be fully able to do given that their profit margin per iPhone is more than double that of other phone manufacturers.

4. “Green Bubbles”

The third complaint is that Apple doesn’t just attract users to their ecosystem with superior products, they actively work to “[drive] iPhone users away from products and services that compete with or threaten Apple”. This is where the complaints about Messaging, Smart Watches and Digital Wallets come into play. Let’s start with messaging.

In 2022, Apple’s CEO Tim Cook was asked whether Apple would fix its broken iPhone-to-Android messaging. “It’s tough,” the questioner said,” not to make it personal but I can’t send my mom certain videos.” What did Tim Cook have to say in response? “Buy your mom an iPhone.” A line that will, hopefully, haunt him forever.

The DOJ’s complaint about iMessage is two-fold. In Apple’s own messaging App, they allow both carrier-based messages (SMS) and more complex messages when you contact someone else with an iPhone. This means that, using iMessage, you can literally contact anyone with a phone number. But Apple does not allow third-party messaging apps to use SMS, meaning that you can only reach people who have signed up to use that same app. Through this and other methods, Apple allegedly degrades apps created by their competitors to encourage people to only use their own default.

The second iMessage complaint relates to the famous “green bubbles”. If an iPhone user messages a non-iPhone user, the conversation thread appears as green, rather than the usual blue, and the functionality is severely limited with pixilated videos and unencrypted messages. Now, I don’t think it’s crazy to change the bubble colour to indicate when messages are less secure, but I do think it’s crazy that Apple is choosing to make these messages less secure. They’re still using SMS rather than RCS, the industry standard for carrier-based texting, which would allow encryption and higher functionality no matter who you’re messaging.

SMS is an ancient technology that we’ve long-since outgrown and yet Apple makes you use it if you’re texting anyone without an iPhone, making the conversation less secure and convenient for everyone involved. Why? To quote from the complaint: ”This signals to users that rival smartphones are lower quality because the experience of messaging friends and family who do not own iPhones is worse—even though Apple, not the rival smartphone, is the cause of that degraded user experience.”

Hey, isn’t that what Windows did with QuickTime? Apple has been able to fix this problem for years but it’s not been in their best interests because it would make it easier for “iPhone families to give their kids Android phones”. The DOJ references user surveys that reveal that “one of the biggest reasons iPhone users do not switch to rival smartphones today is to avoid the problems Apple has created for cross-platform messaging”

Now, to be fair, Apple has finally stated that they’re going to incorporate an older version of RCS into iMessage, but make no mistake, this is solely in response to regulatory pressure — and at the time of this writing, they haven’t actually done it yet. Given their track record of malicious compliance I’m not convinced that they will actually fix this problem in any meaningful way and, regardless, third-party apps still won’t be allowed to use RCS or SMS.

Polymatter calls the whole messaging argument weak, and says that green bubbles serve a purpose because they let you know that the conversation is unencrypted. This completely misses the point, which is that Apple chooses to make the conversation unencrypted (something that doesn’t come up in the Polymatter video).

If I’m honest, I think the argument that any app should be able to handle SMS isn’t the strongest. I can see the benefit of having one dedicated app for texting, as opposed to online messaging. But with iMessage, Apple has bundled a separate service, which would otherwise have few advantages over competitors, into their dedicated texting app. That makes the DOJ’s argument stronger, and I think the real kicker is that they made this the default messaging app. Install whatever apps you want, but if you try to message someone through your contact list, Apple takes the reins – and of course you’re not allowed to change the default. Except in the EU because we decided that’s illegal.

4. Smartwatches

I’ve been pretty hard on Apple so far, so let me tell you a quick story that will doubtless put a smile on Tim Cook’s face. In a former job of mine, I won an award for fulfilling some corporate value, and they gave me an Apple Watch. I would have preferred a pay increase, but I thought, at least it’s something? Except I was surprised to learn that my new device wouldn’t function at all with the Android phone I used at the time. It’s a big part of why my next phone, was an iPhone. While this was annoying, it didn’t seem illegal (not with current regulation, anyway), but let me tell you a different story:

Years ago, for my partner’s birthday, I got her the Fitbit that she wanted. It worked great and she loved it, until she got an iPhone. At that point her experience became glitchy, it wouldn’t sync properly and she’d always be missing steps in the Fitbit app, which would often crash. It was such a bad user experience that she eventually caved, bought an Apple Watch, and gave the Fitbit away.

It’s fine if devices from other companies work badly with iPhones if this is the fault of the other company, but if Apple intentionally limits the functionality of devices from other companies, as the DOJ alleges, then that does seem genuinely anticompetitive. And it’s simply a fact that they don’t give third parties access to the advanced APIs they use for their own products, so for smartwatches you can only respond to a message or accept a calendar invite using an Apple Watch. It’s not because Apple tech is superior, it’s simply because Apple doesn’t allow it. They also stop your third-party watch from easily maintaining a reliable connection with your iPhone, which is probably why my partner was missing those steps. Polymatter has this to say:

“The DOJ is right. This is pretty clearly anticompetitive.”

That’s great, let’s move to the next section —

“a completely level playing field would mean less of the deep integration that consumers love about apple”

…what??

“The DOJ never acknowledges this trade-off”

Maybe that’s because you made it up, Mr. Polymatter? No one is asking Apple to make their products work less well with one another? Or to remove features that they’ve built? They don’t even need to divert their money and attention into making products from other companies work better on their platform — all they need to do is open their APIs and other companies will work to make it function because they want access to Apple’s userbase.

5. Digital Wallets

Apple has a digital wallet that you can add your card details to and use to pay for things in everyday life, using the iPhone’s NFC chip. Apple have decided not to let any other developer to use this technology, even though there’s no reason that another app, like Google Pay or one created by your bank, shouldn’t work on iOS. Why have they done this? It’s the same reason as always: Money. For every credit card transaction, Apple charges banks 0.15% – with more and more people going contactless and leaving their wallets at home, Apple estimates that such fees will earn them around 1 billion dollars in revenue in 2025. Note that payment apps from Samsung and Google are free to issuing banks.

You might be saying “Jakob, as long as this fee affects my bank and not me, I don’t give a shit. Besides, don’t you want banks first against the wall when the revolution comes?” Valid points. But setting aside the fact that these fees do get passed on to you, let’s look to the future that Apple is trying to build. They want the Apple Wallet to be the tool you use for everything from shopping to opening your car, using public transport, getting on a flight and identifying yourself. Right now, if I got an Android phone, I’d be OK as I still have physical cards that I could put in an Android Wallet, but in the future that Apple imagines, that would not be possible, just like my Apple Watch would be useless without my iPhone.

Banks are rightly concerned. Seven major banks have come together to try to compete with their own digital wallet (PAZE) but they have little chance without access to the tap-to-pay technology that Apple is hoarding. Simply by limiting this access, Apple can extract monopoly rents from banks for access to the Apple userbase, while at the same time making that userbase more reliant on Apple in the long-term. If Apple had actually produced a superior digital wallet that people chose over competitors, this would not be an issue – but it is only superior, and Apple can only get those extra billions, by locking competitors out and limiting how we use the expensive-ass pieces of tech that we fucking own.

I’m no staunch defender of banks, but I don’t think that Apple eating up more and more of the overall economy would ultimately be better for “consumers”. In the end, we will be the ones paying; that’s how monopolies work. They undercut competitors and leverage their size to grow, and then they drive up prices. It may sound like a good deal in the short run, but someone ultimately has to pay because the goal under capitalism is always unfettered growth.

Just one more thing on Wallets – in an ideal world, my bank and I are the only ones that know my card details. That certainly seems like the most private and secure option. But if I want to tap my phone to make a payment, Apple won’t let my bank manage that transaction – the company inserts itself into the process and demands that I share my card details directly with them, adding a fun new point of failure. Apple often touts itself as a champion of privacy but, something’s not quite adding up here…

6. The Privacy & Security Argument

I’ve always been a privacy advocate, and I find the Surveillance Capitalist society we live in absolutely absurd and mind-numbingly infuriating, so I’m onboard with the small wins Apple has given us to support their marketing claim of being privacy-focused. No other tech company has so successfully tied their brand to the value of “Privacy”. But make no mistake; this is marketing. No corporation’s ultimate goal is privacy, it’s to make money.

For example, I like that you can easily turn off tracking for most apps in iOS – generally speaking, anything that upsets Mark Zuckerberg is probably a good thing – but this is no great sacrifice for Apple. They are simply preventing other companies from modifying the behaviour of their users; something Apple prefer to do themselves. They spend a lot of money advertising themselves as privacy champions while choosing to compromise your privacy and security in order to up their revenue. We’ve already talked about how:

- Apple forces you to use outdated, unencrypted messages when texting in order to get you to to “buy your mom an iPhone.”

- They force you to share your financial information with them if you want to use your phone to tap-to-pay, even though that information could easily remain confidential between you and your bank (or a different third party).

- Apple accept billions of dollars from Google to make them the default search engine on iOS, even though Google are the original surveillance capitalists and there are many more private search engines, a fact Apple is well aware of.

That last one is part of why Google has already been judged to be an illegal monopoly in a US court. We’ll see how that shakes out in appeals but, hey, it’s a start – and maybe, just maybe, these could be the winds of change.

7. The Winds of Change

Though I agree with a lot of what the DOJ is saying, I don’t think their case is a slam dunk. It would be a clean case if Apple simply banned cross-platform smartwatches, for example, but Apple has gone for a subtler approach, exercising control by tangling you up in fees and red tape. The DOJ alleges that the five items in the Polymatter video are only examples of an illegal pattern of behaviour that has a cumulative anti-competitive effect. They also reference Apple’s long history of malicious compliance – once cornered by regulators, Apple will “allow” something but make it so difficult or expensive that it becomes unfeasible. For example, there’s the Spotify problem that Polymatter brings up:

”You can’t subscribe to an app like Spotify in the Spotify app. Until recently, Spotify was prohibited from offering a button that takes users to its website where they can subscribe. Spotify is banned from telling you this with words. It can’t even communicate freely with its own users.”

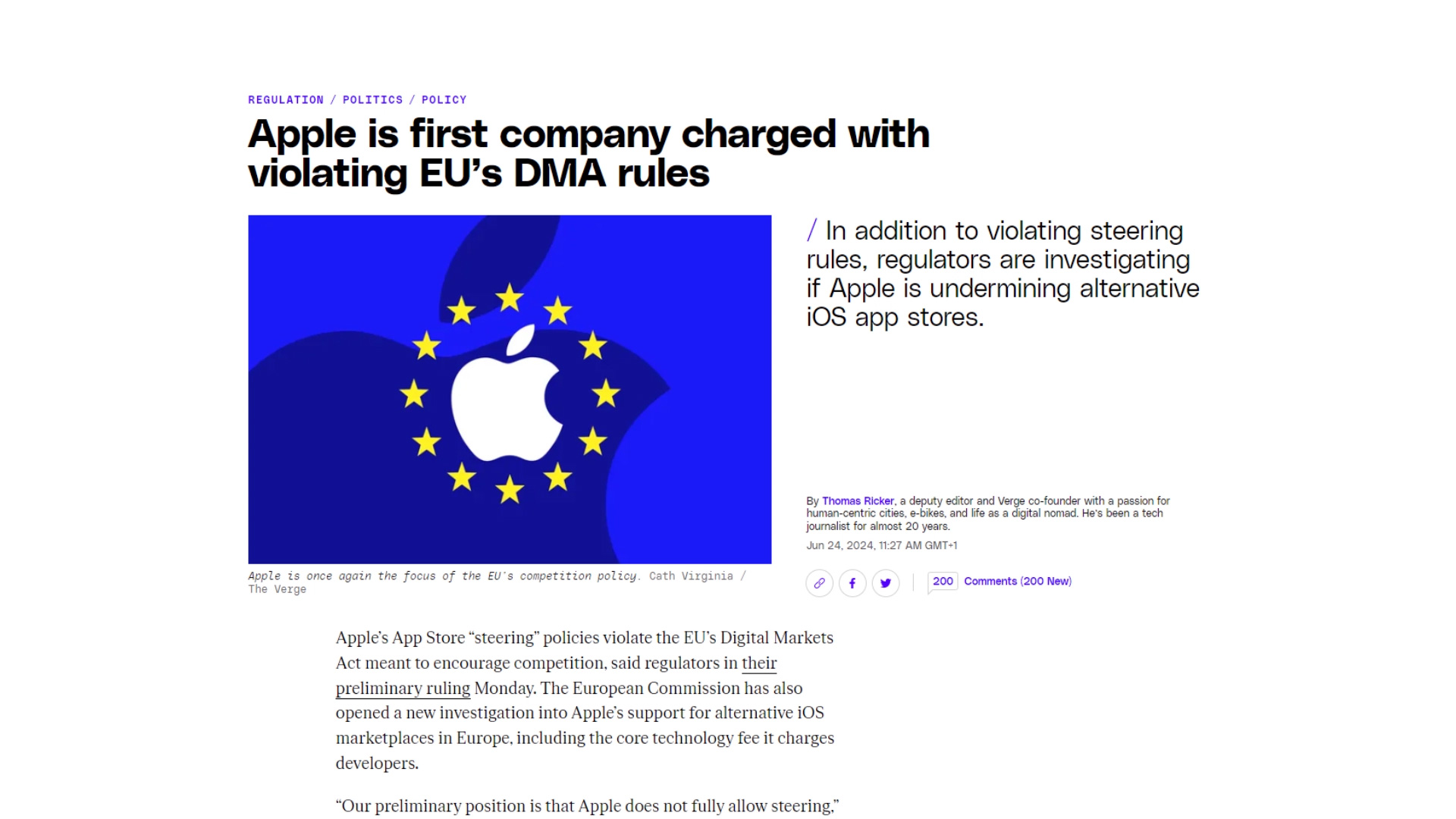

After a 5 year legal battle, the European Commission ruled against Apple on this matter, slapping them with a 1.8 billion EUR fine. Apple’s response was to change their rules so that, yes, you are now allowed to include an external link in your app – but they also invented a new 27% “core technology fee” for payments made outside the app, hardly an improvement over the 30% fee in the app. When Spotify decided not to include a link and instead just display the lower prices you could pay via your web browser, Apple said no, we’re not going to allow that – you have to pay 27% or you can’t even tell people the price in your app. So the matter has now gone back to the European Commission.

By the way, Polymatter says that this Spotify problem is only brought up once in the complaint, which is technically true, but whole the source of the problem is the 30% Apple tax which is referenced throughout the complaint, and ignored by Polymatter, who instead brings up measures that Apple has taken recently to shift their policies. And it is true that Apple is currently making moves to:

- Adopt RCS (in iMessage only)

- Allow other app stores (in the EU only)

- Allow web browser to use their own engines, rather than apple’s webkit (in the EU only)

- Allow changing default apps on phones (in the EU only)

But it’s also true that this is solely in response to regulatory pressure, specifically the introduction of the Digital Markets Act in the EU, which has made many of Apple’s behaviours outright illegal. It’s why many of these things are only happening in the EU, and even here, regulators will need to drag Apple kicking and screaming every step of the way. For example, while they’ve been forced to allow other app stores on their platform, Apple has invented another new fee to charge for installations and updates of any apps that get popular in these new app stores. As a developer, you would get charged 50 cent per user over a million, even if your app is free or freemium, meaning that if you have 10 million downloads and 10 million in sales, Apple would charge you $515,942 per month, adding up to over 6 million per year, so 60% of your revenue instead of 30%. And I know these numbers are correct, because Apple helpfully created an official fee calculator.

This is a deterrent to get people to stay in their lane and do what Apple wants. That is what Apple does. They fight for the right to subjugate their competitors, drain them of resources with bogus fees and use Apple defaults to edge them out. You can be damn sure that Apple doesn’t charge itself a 30% fee when you set up Apple Music instead of Spotify!

Because Apple holds this dominant position, and because they’re the highest valued company in the world, they can afford to be this belligerent. Other companies can’t put up a fair fight, meaning that it’s up to our governments – and we are, right now, seeing land mark cases against giant tech companies. But policymakers around the world will only continue this work for as long as it is popular, which is why public opinion matters, which brings us back to Polymatter and the question of bias.

8. Polymatter Matters

For explainer channels with high production value it can be easy to forget that there’s always a person and a perspective behind what you’re consuming. Especially when the topics seem fact-based, like Polymatter’s “How Cruise Ships Work” and “Why Car Dealerships Exist”. But Polymatter got interested in geopolitics and business via high school debate, where, of course, your job is to write a convincing case. I think the backlash against Polymatter’s Apple video comes from a whiplash of people realising that someone you thought was just “telling you about something” is actually setting out to convince you of something.

To me, Polymatter sounds like someone who has only ever owned an iPhone. I could be wrong about that, but that’s the type of thinking that infuses the video. For me, it’s an un-relatable perspective, as someone who’s presumably a bit older and from a country where Apple doesn’t have a smartphone monopoly. I don’t think Polymatter’s video is intentionally biased, but rather I think it shows the power that large corporations wield in influencing us. Your culture and background is always going to affect how you think, and when corporations get powerful enough to shape law and culture, that can make their influence, though ever-present, seem invisible. Does the fish know that it’s in water? Or, in this case, does the fish know that the stream it swims through is designed by decades of neoliberal policies aimed exploiting common people in order to centralise wealth and power in a class of corporate elites?

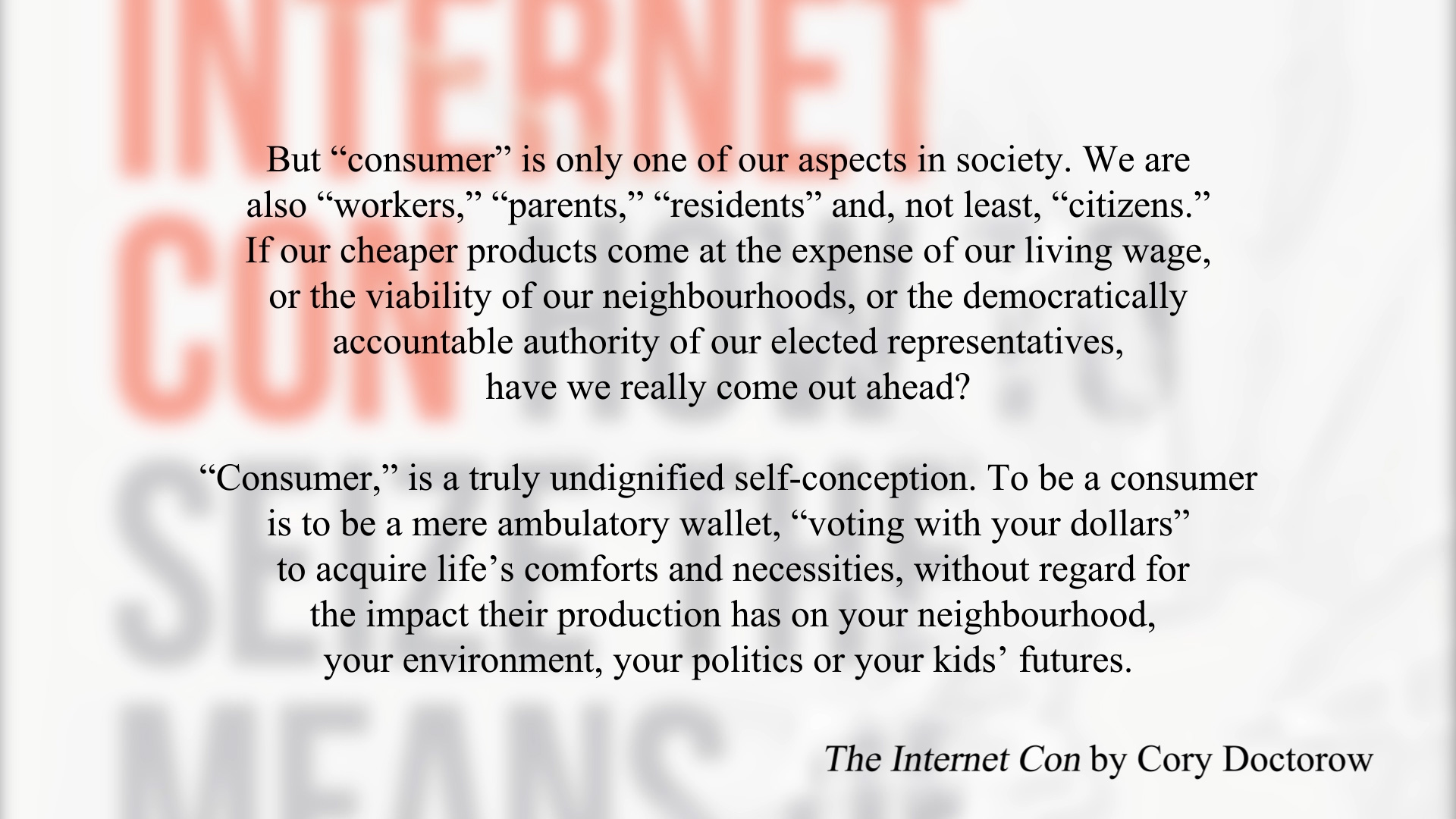

I’m very tempted to get into the history of antitrust in the US but after my Knight’s Tale video my partner has threatened to move out if I spend another six months on one single topic, so I’ll leave that for a potential future video, but I do want to clarify why I think the question that Polymatter poses, is a wrong one. When scoping the video, Polymatter says that they’re going to focus on the effect of the suit on “consumers”. But, to quote Cory Doctorow:

Even if you want to focus just on prices, remember that monopolies up their prices when alternatives have been smashed. That’s simply how they work. Polymatter calls the suit tragic, saying it focuses on the wrong things, but don’t underestimate the effect even of an imperfect antitrust suit. In 1970, the US DoJ sued IBM, the big tech monopoly of the time. After a 12 year legal battle, IBM won, but they emerged a transformed company, much less eager to take what could be perceived as anti-competitive actions. That’s why, when they made their PC in 1980, they didn’t tie their own software to the hardware – instead they looked around for someone else to supply the software and what they found was a young, small company by the name of Micro-Soft.

So stay with me here:

- DOJ v. IBM in 1970s ➜ Microsoft flourishes in 1980s

- DOJ v. Microsoft in 1990s ➜ Apple flourishes in 2000s

- DOJ v. Apple in 2020s ➜ ???

What new revolutionary technology might this lawsuit help bring about? If you think cool new tech can only come from Apple, please consider that they spend more than twice as much on stock buy backs as they do on research and development. In the future that Apple wants, they will use their monopoly to continue gobbling up the market and remain the highest valued company forever. But I don’t think that would benefit us, neither as consumers nor as human beings eager to develop our culture, society and planet with revolutionary new technologies. In one future, Apple wins. In another, we might.

What future do you want?

Video published September, 2024

Text published March, 2025