How to Write Fight Scenes

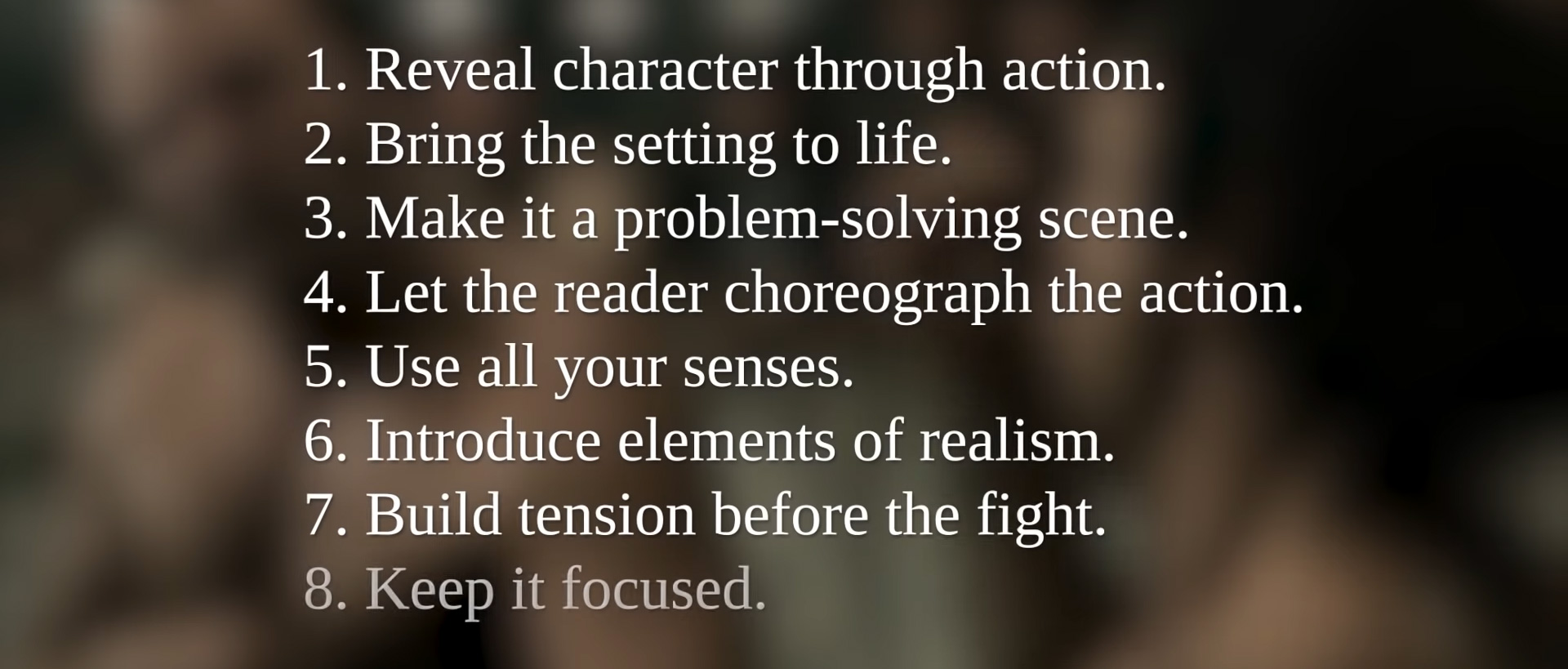

Since tales were first told, stories of duels and battle have been some of the most enduring. It's where complex conflicts boil down to a simple who wins/who loses, and the tension of that question sits at the foundation of whole genres. And yet, skipping or skimming fight scenes is more common than you might think. Especially in written fiction, which is the main focus of this essay, fight scenes run the risk of losing the reader. So how do you avoid that? That's the question I hope to answer today – how can you write a fight scene that no one would ever skip? Researching why people skip fight scenes, I found some recurring complaints. From those, I made a list of 8 things that often go wrong, and we'll go through those problems, one by one, to see how they can instead be turned to your advantage.

It feels seperate from the story

One central reason people skip fights, is that the story is put on hold, and stands still until the end of the scene. This is a very video game way of writing; the story's happening, but then it stops, and there's a challenge to overcome before the story continues. This works in a video game because you're facing the challenge yourself but that's not the case in movies and TV. So if the script just says "they fight" who could blame you for going to make a sandwich and then popping in to see who won?

In written fiction, which is the main focus of this essay, we don't even have the advantage of a visual spectacle. So how can we make the fight feel like the fight is part of the story, not apart from it?

Solution: Reveal character through action.

Well, by revealing who your characters are, through their actions. A tense moment of physical conflict is likely to show you a lot. Your characters can even find out things they didn't know about themselves. Sure, you can do big, dramatic reveals but there are subtle ways to think about this.

For example, Stephan Krosecz made a breakdown of the first Pirates of the Caribbean movie (Pirates of the Caribbean - Accidentally Genius), paying particular attention to an early fight scene that tells us a lot about Will and Jack. Details are given in dialogue,such as the fact that Will is a skilled blacksmith's apprentice, but there's more important stuff revealed; things they don’t need to say out loud because they show you. Like the fact that Jack will trick his way out of any situation. And that Will does what he thinks is right even when he has to pay a massive price.

I suggest watching the detailed breakdown in Stephan Krosecz's video -- although you probably have given that it has over 7 million views.

Who wins the fight is important, sure, but it's how you beat your opponent, or not, that reflects your personality and development.

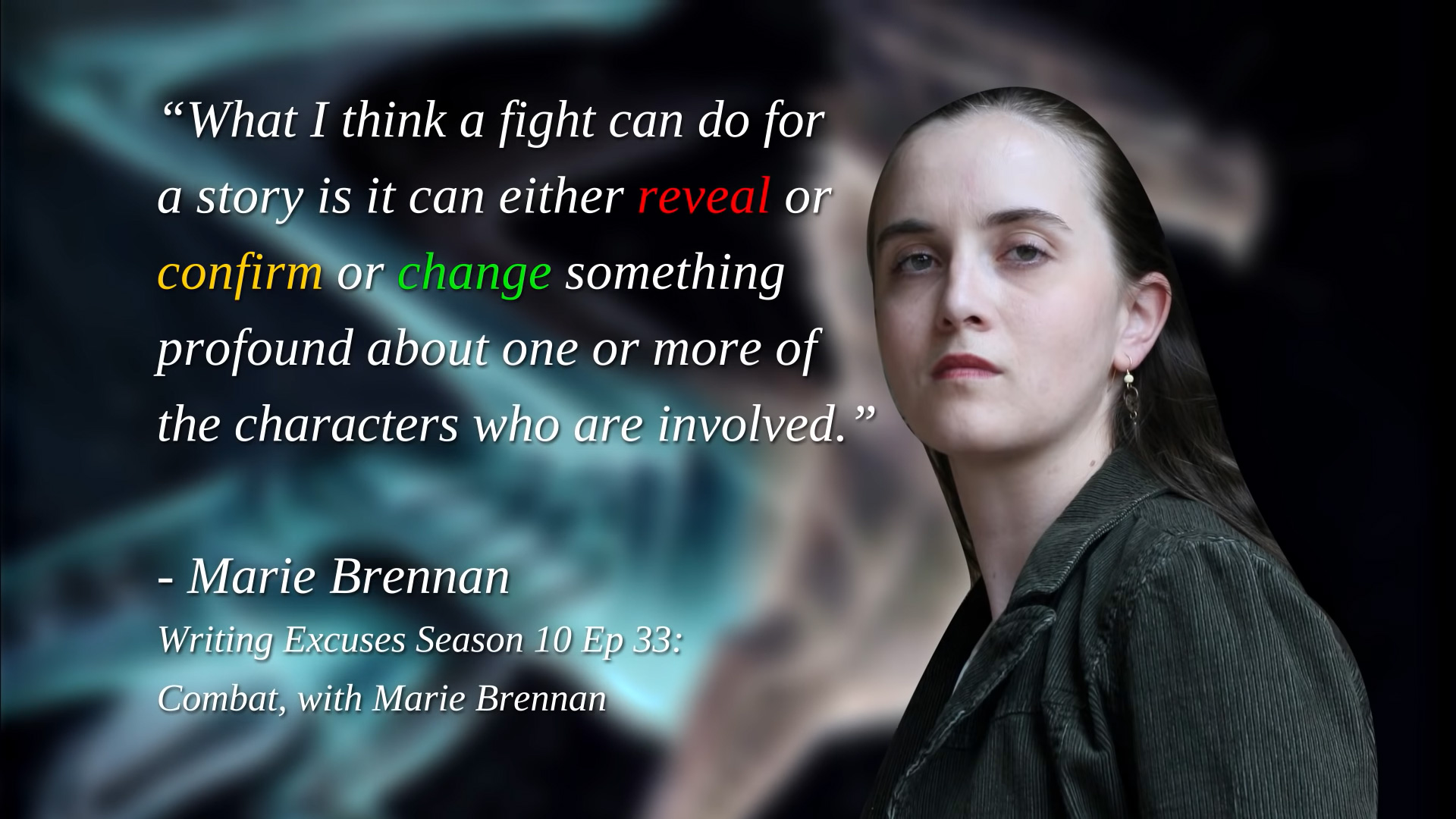

Reveal, confirm, change from the Marie Brennan quote above gives us the bones of a story: Reveal who your character is in a first fight, confirm who they are in a second, and show their change in a third. If you intergrate your fight scenes in such a way, they become essential and pivotal to the story, rather than seperate.

I can't follow what's happening

Being able to follow the action is hugely important, otherwise your fight will just be a big mess. It's hard to care, and keep caring, when you're being assaulted with something unintelligeble.

In my opinion the solution is not to go into massive detail on what's happening (in fact, that's likely to make things more convoluted) but rather I'd suggest paying attention to the setting of your fight.

Solution: Bring the setting to life

Unless it's pistols at dawn in the desert, or a never-ending tournament like in Dragonball, the space will have a huge impact on how your characters achieve their goals. For this reason you should probably make a map of the location, to keep track for yourself. You don't need to explain every inch to the reader, but you need to establish the space.

Show the location before the fight because during the fight there won't be time. Your characters are likely to use any advantage they can get from what's around them. And if you establish those things before the fight, it won't come out of nowhere when they're used to turn the tide.

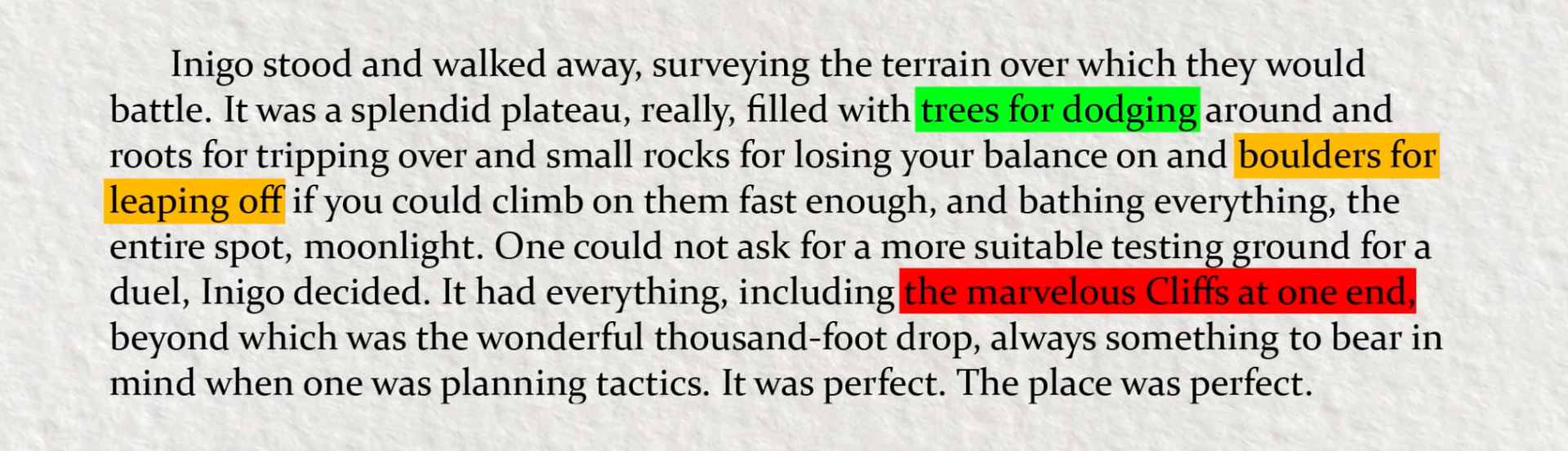

There are many good things to be said about the iconic fight between Inigo Montoya and Westley by the Cliffs of Insanity in the Princess Bride, but let's focus just on the setting. In the book, Indigo takes a moment, a single paragraph, to survey the battleground. There's the rocky wooded section, the open space, and the cliff. which is especially well-established as a danger due to the long climb.

When the fight starts it moves between the trees, the open ground, the cliffside, showing the fighter's strengths and weaknesses in different areas. And it's easy to understand that whoever gets pushed closer to the cliff is at a disadvantage.

A fight can also reveal new things about the setting. Are bystanders egging the fight on or shutting their windows and staying indoors? Are they ignoring it, taken aback and unsure, or are they rushing in to pull the combatants apart? It's all very well to say "yes, folks round here hate violence" but it's only when a fight breaks out that you see if that means people run away from violence, or towards it, and that's likely to stick in your reader's mind much longer.

The action is boring

It doesn't really matter how good your setting is if the action starts and it's all kick, punch, kick, punch, kick, punch. A fight feels static if it lacks a distinct punc-and-pull of will.

In short, the word scene is more important than the word fight.

Solution: Make it a problem-solving scene

First, make sure it's clear what problem the main character wants to solve, and why.

Here are some simple, potential problems: I want to get past you to save someone; I want to defeat you to prove something to myself; You have a thing I need, and the ever classic; I don't actually want to fight you!

Within the scene, have your characters try and fail to achieve their goal several times. Make them pay a price for each failure and escalate the conflict. Get inside your character's head and show what's happening there as they get closer or further away from their goal.

Super Eyepatch Wolf has an interesting video on this. Though focused on anime, I definitely recommend his "What Makes" series to anyone interested in writing as it delves into the reasons why some things work, shining a light on universal building blocks that all writers need.

Comparing a fight to a game of chess, Super Eyepatch Wolf divides the writing into a technical narrative (everything on the chess board) and an emotional narrative (everything in the players' head) including what brought them there, and what victory or defeat would mean to each one.

Both narratives need to come together and work in unison. And when they do, your readers are not going to zone out because there's an engaging dialogue going on, even if words aren't spoken.

Too many details!

If you dive too deep into combat technique you might achieve a very niche appeal while leaving the rest of your potential readers, confused or bored.

Your job is not to reproduce the fight in every intricate detail; it is to capture and convey the feeling of the fight, and the best way of doing that is to let the reader work for you.

Solution: Let the reader coreograph the action

Without your reader, your story is just scribbles on a page. They are the ones who bring those scribbles to life and they come willing to do so, eager to imagine these wonders. All they need are some cues to get them started. That's why you don't give every detail in any situation; you leave things to the reader's imagination, and this works especially well in fight scenes.

"Show them early on in the fight how each weapon moves through space—make that vivid and visceral. Make the reader feel as if they could actually pick up that weapon and defend themselves [...] The reader will then be able to fill in the action while you describe what your characters are saying, what they’re thinking, and what’s showing on their faces. In other words, help the reader to choreograph the fight so that you can spend your time on the drama." - Author Sebastien de Castell

I think this is great advice. Go viceral first, set the tone, then feel free to abstract out and let the reader take the reins.

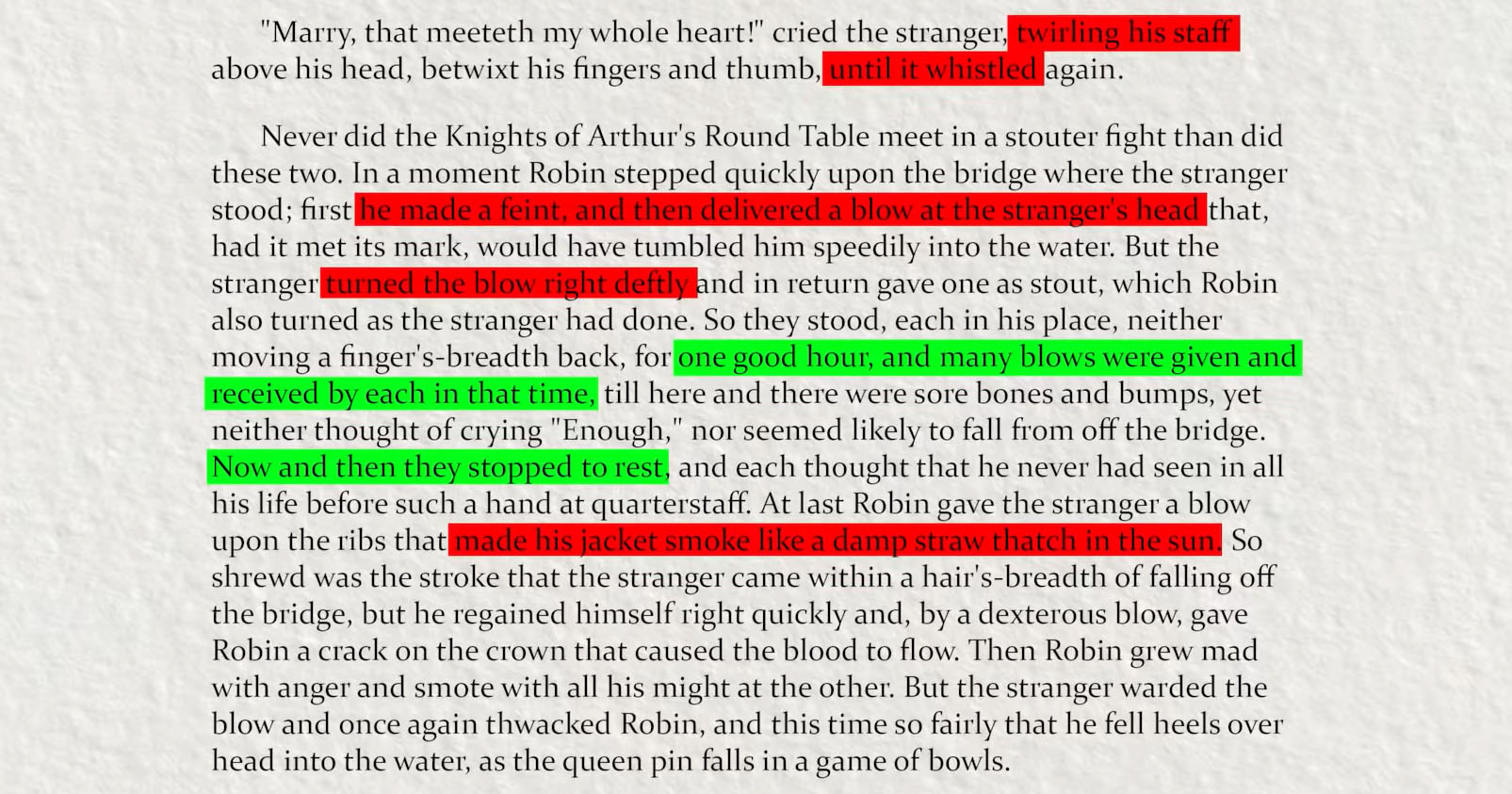

Below is an example from "The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood" by Howard Pyle. It's his version of the fight between Little John and Robin Hood on a log of wood over the water. There's details that put you in the moment (red) and abstract sections that let you fill in a lot of blanks (the green). Note that the actual fight is less than a paragraph, and that doesn't make it any less memorable of an encounter.

Visual fights are more exciting

We're a visual generation. My video essay is going to be viewed a lot more times than this text version is going to be read. And when we get all our storytelling training from films and TV, it's going to slightly mess up the way we write.

There's nothing wrong with studying and working in different mediums but be aware of the strengths of each one, and don't play to the strengths of film if you're writing a novel, because prose has distinct advantages of its own.

Solution: Use all your senses.

Almost every fight scene describes the visuals, what the fight looks like, and sounds, like dialogue and the crunch of breaking bones. But seeing someone get pummeled is different from feeling it.

What is the touch of asphalt like, when your nails scrape over it as you claw to get away?

What about the stench of manure from the nearby stables?

Your opponents cigarette smoke tickling its way up your nose?

Taste can easily get cliche; how often have you read that someone tasted blood in their mouth? I've written that too, we probably all have, but how about tasting the mud as you're pushed down?Tasting the slick sweat as you bite into your opponents hand in one last desperate attempt to escape.

Boiling it down to the senses is appropriate because. In a stressful situation like a fight, there shouldn't be long flowery description. Your body is getting input faster than your brain can put it together, and using raw sensory data is a great way of pulling the reader into the moment.

Films are limited to visuals and sounds, so you actually have an advantage because your only limit is the reader's imagination.

And by the way this also means you have an UNLIMITED SPECIAL EFFECTS BUDGET!

This feels unrealistic

Treausre Island isn't a scientific report and Die Hard isn't a documentary. They are roller coasters that don't aim to reproduce reality with perfect accuracy.

So your story doesn't need to be real, but it does need to feel real. And that might be doubly true for fight scenes. If we don't believe there's any danger, it takes the air out it.

Solution: Introduce elements of realism

Here are some things that might annoy martial artists who read your story, as told by Wesley Chu, author, former stunt man, and martial artist:

1. Fight scenes don't last forever. Real fights are fast and brutal.

2. Weapons aren't that light. Unless you're fencing, you're going to want to use your whole body.

3. Training takes time. As Weasly said, during his first two weeks of martial arts training, he just got to walk in a circle. The next two weeks, he walked the other way. Because it's all about building from the ground up, and that takes a lot more time than we think.

4. Then there's recovery time. If you've ever had an injury, sure, the pain sticks in your mind. But the reason we end up frustrated afterwards is the slow, gruelling recovery. Yes, in an action story this might be better off ignored, after a quick "improvised bandages" scene. But in many cases it can be a missed opportunity.

No one would accuse A Song of Ice and Fire of being completely realistic, and the tv adaptation even less so, but having a character perish unexpectedly from an infection, or brought down not by his mighty opponent but by a spear from the back, gives you a certain degree of credibility.

Sometimes you do want things to be larger than life, but sprinkling in some of these elements can make the conflict more tense, dangerous, and interesting.

There's no real reason for the fight

Sometimes character crash together for flimsy reasons because "wouldn't it be cool if" they did. And whenever character motivations bend in unnatural ways to build a situation, it's going to feel wrong.

But that's not going to happen if you root the conflict in who the characters actually are and if you show what they want before they even lay eyes on each other.

Solution: Build tension before the fight

It's like the old Hitchcock bomb thing where if you let the viewer know there's a bomb under the table, they're going to be on the edge of their seat, even if the characters don't know. The bomb equivalent here is to let the reader know a fantastic fight is coming; that will get them turning the page. And you don't need to hammer this home, because the reader is smart.

If you show a badass fighter who wants something that's completely the opposite of what your protagonist wants, that alone will get us imagining and anticipating what will happen when those two forces come into conflict, and it's all rooted in believing in the wants and needs of those characters. If they are believable, the fight will be too.

If we're already excited before the fight starts, the fight itself doesn't need to be drawn out.

Which brings us to...

It's too long!

As mentioned, one element of realistic fighting, is brevity: Fights often end fast.

So if all else fails, make your fights shorter. It won't make them less tense, not if they have proper build-up, and no one has ever skipped a fight scene because it's too short.

But the solution is not to make it one sentence either, so where do you draw the line?

Solution: Keep it focused

In a fight, your characters will be more focused than usual. Your writing should reflect that, with short words, short sentences.

Instead of "they pulled at one another, each trying to get the upper hand." you can simply write "They grappled."

Online you'll find lists of forceful-sounding words. And I'm by no means saying you should stuff all these in but they're good building blocks for short, concrete sentences, and if you build a scene out of sentences like that, you're well on your way.

Conclusion

We started with 8 problems, and now we have 8 opportunities.

Do you need to hit all of these in every single fight scene? No. But if the fight doesn't reveal anything new (no. 1) maybe you should make an extra effort to keep it focused and brief (no. 8). If the fight doesn't have any realistic elements (no. 6), highlight how the characters strive towards their goals (no. 4) because if the conflict works, we'll suspend a lot of disbelief.

As always you're not going to write anything perfect in a first draft. I'd advise flailing at the topic as much as possible. If you're uncertain, write a lot of fight scenes. Pick one of these tips and really focus on nailing that aspect. Because if you really want something, you need to fight for it.

So pick up your pen, and start the battle.

Jakob Burrows

Text published March, 2021

Video published April, 2018

Sources

"Pirates of the Caribbean - Accidentally Genius" by Reality Punch Studios

"What makes a fight scene interesting?" by Super Eyepatch Wolf

"5 Essential Tips for Writing Killer Fight Scenes" by Sebastien de Castell

"Writing Excuses Season 10 Ep 33: Combat, with Marie Brennan"

"Writing Excuses Season 8 Ep 43: Realistic Melee Fighting with Wesley Chu"