In Defence of Buffy Season 1

I used to warn people about Buffy the Vampire Slayer Season 1. I’d call it a slog, a rough start, something you have to suffer through to reach the true brilliance of the show — and, to be fair, that’s often the case with classic TV. A long-running show will, if it’s lucky, be remembered for its highs and not for its lows, but things do often start out low as a show figures itself out. Sure, you might have a fantastic script, but you won’t really know what a show is until the rubber meets the road. The iconic comedy duo of Community was supposed to be Troy and Pierce, after all, and it was only halfway through season 1 that they figured out the incredible chemistry of Troy and Abed, and started writing that into the show instead.

Screenplays are less like novels and more like blueprints, and at the start you haven’t built anything yet, so the first season of a show is often written “blind” in a way that later seasons simply are not. So, just as you might see big changes comparing a pilot to episode two, a first season can act as a pilot for the rest of the series; a starting point to be improved upon.

And there are, of course, many ways that Buffy Season 1 might have been improved upon, including special effects and fight choreography, factors that couldn’t yet match the high ambition of the script. Even the most die hard Buffy fan will admit that, compared to later seasons, Buffy Season 1 is different and I’ve even seen people recommend which episodes to skip to get to the good seasons, something that might well have seemed reasonable to my past self. However, I wrote this essay because on my most recent re-watch I had an epiphany, and it is this: My past was an idiot, Season 1 is just as good as later seasons, and I got the proof, baby!

WELCOME TO MY TED TALK

Welcome to the Hellmouth

From the very first shot we’re introduced to a Sunnydale High wreathed in shadows, with a camera that meanders through the halls in the point-of-view tradition of 80s horror flicks. Welcome to the cold open, the bit before the intro, the part where someone is usually murdered! That’s the main function, teasing a mystery to catch your interest, but a great cold open should also be thematically relevant. Screenwriting 101 will tell you that the first scene should work as a microcosm of the whole story, just as the first page of a novel gives you a good idea of what to expect, and the first scene in Buffy does just that as we’re introduced to Darla, a seeming victim who turns out to be the monster – and this tells us exactly what to expect, not just from the episode, but from the whole show.

The creation of Buffy started with the idea to invert the trope of ”the little blonde girl who goes into a dark alley and gets killed in every horror movie”. In Buffy, that girl is the hunter, and this is only the first in a cavalcade of tropes we’ll be playing around with. Hell, this show is probably the reason you know what a “trope” even is, as TVTropes.org was created specifically to keep track of how Buffy played with genre conventions, after which the website branched out and became a repository that covers all known media from Gilmore Girls to Gilgamesh.

A lot of writers would do well to remember that just throwing a bunch of tropes together does not automatically create a story. And the basic conceit of “what if that blonde girl was actually the hunter” — that’s not a story. It’s a twist, but it’s not a foundation that you can create episode after episode from. For that you need a springboard, a mechanism by which you can launch a thousand plots. And in Buffy that mechanism is: What if that slayer had to fight a different monster every week? Now you have an external plot but that’s still not a story because there’s nothing internal happening there. For that, we need to get to the foundational mythic core upon which all of Buffy is built. Which Buffy’s mother helpfully lays out in the two-part pilot:

“Everything is life and death when you’re a 16 year old girl.”

That right there is the thesis, because each monster that Buffy fights serves as a heightened version of some real-life relatable problem that teenagers go through. That’s what all good fantasy does; monsters are always stand-ins for real-life problems, whether that’s Godzilla representing our fear of nuclear fallout or witches representing our fear of, you know, women. If a hero fights a monster without a real-life anxiety attached to it, that’s just a pointless action sequence, but when a hero can punch a monster and, at the same time, punch the concept of bullying — well, hot damn, that’s what storytelling is all about!

For example: In the third episode, The Witch, Buffy perceives her mother as overbearing, attempting to take over her life. Turns out there’s another girl, Amy, whose mother is literally taking over her life, having Freaky Fridayed the two of them with dark magic so she can re-live her glory days — and she’s not afraid to set fire to a few cheerleaders to get there. Thus, the natural, every-day problem that Buffy is dealing with has been elevated into the supernatural, allowing her to physically fight and defeat it, and bringing us neatly to a reconciliation with her mother at the end, as Buffy has learned something through this experience. Now, that’s a story!

Bullying is tackled in the sixth episode, The Pack, where the idea of teens acting despicably due to pack mentality is elevated into the supernatural when Xander is inflicted with a Hyena spirit, and in Out of Sight, Out of Mind, a perpetually ignored girl feels invisible to her peers, and the demonic radiation of the Hellmouth causes her to become actually invisible, which drives her to take revenge against those who ignored her. Of course, in that episode, Buffy herself is dealing with feelings of alienation; her real-life problems let her identify with her opponents, which allows her to change and grow once she understands the psychological impulse of the monster and either kicks its ass or rehabilitates it (often both).

Look, I know I’m not breaking any new ground here, you probably knew that Buffy fights teenage problems made manifest and if you didn’t, you could grasp it by watching pretty much any episode. That deeper meaning might not always seem so deep (some of the monsters are pretty on the nose) but this central aspect still infuses the show with a mythic quality. Myths are our way of making sense of the world, and through the show we follow Buffy as she makes sense of everyday problems by punching them in the face. The fact that these are relatable problems we all have to face when growing up is what makes it such a highly resonant show.

The coupling of the monster stuff and the teen stuff allows this show to create something new, where each elevates the other. We get the best of both worlds, as the sun-drenched Sunnydale High stands in contrast to world of shadows in which the teenage subconscious goes into battles far greater than what can be seen on the surface. Teen dramas and creature features both have a plethora of conventions to pull from and in Buffy Season 1 these genres come crashing together in such a spectacular fashion that they fuse, creating something entirely new. It might not seem so revolutionary now, but the list of shows, movies, comics and other creative works that wouldn’t exist at all without Buffy’s first season is incredibly long. And of course that list starts with Buffy seasons 2-7.

Because despite any of its faults — which we’ll get to— Buffy Season 1 lays an extremely solid foundation.

The Importance of a Solid Foundation

Later seasons would go on to complicate the relationship between the natural and supernatural world in ways that brought more depth to the storytelling, but none of that would be possible without a solid foundation to stand on. You cannot start out with complexity which, again, is something that modern TV needs to remember.

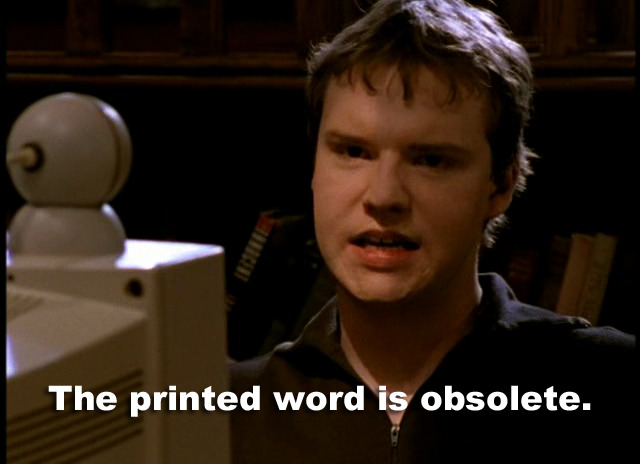

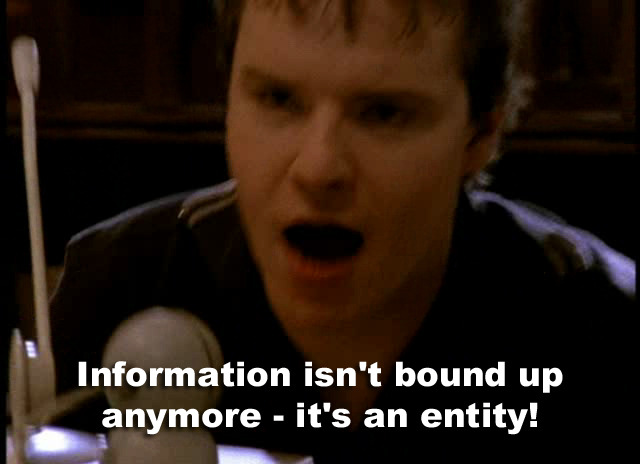

Back in the early 2000s, we were fatigued with shows resetting their status quo at the end of each episode, we longed for longer-form storytelling and our culture has been enriched by great writers pulling that off to perfection, but we’ve also seen how a longer runtime can get squandered. How often have you watched a Netflix show with a plot that probably would have worked well as a feature film, but instead they stretched it into a dozen episodes? The business priorities behind TV production have shifted; it’s now less important to lure viewers back after commercial breaks, and more important to produce an endless stream of CONTENT for people to leave on while they’re on their phones.

Netflix is sending scripts back to writers with requests that the characters announce what they’re doing so that viewers who have the show on in the background can follow along. They’re literally asking writers to tell, not show, because they don’t expect people to pay attention. You might say, “well Jakob, bad shows have always existed, you need to seek out shows that are made for smart people who like to pay attention”. But guess what, most of these “smart” shows people tell me to watch shy away from honest, old-fashioned storytelling and instead rely on unanswered questions and endless flashback episodes in hopes of luring people back with some great mystery. Remember Westworld? I’m proud to say that I saw where that shit was going from the very start — absolutely nowhere!

I bet if Buffy Season 1 was made today, the full 12 episodes would be used to solve ONE mystery, with action set pieces at the end of each episode to make it feel like something’s happening. But that’s not what Buffy is; compared to your average Netflix show, the amount of plot packed into each episode should be overwhelming but it’s not. And it gets the balance between episodic and long-form storytelling just right. Sure, as later seasons got more episodes they could take that further but I’m shocked at the confidence with which Buffy the Vampire Slayer explodes onto the screen in its first season.

They got so many things right from the very start, like the charm, comedy and genuine emotion that Sarah Michelle Gellar brings to the character from the get go. Screw it, ditto that for the whole ensemble cast with Giles’ sincerity, Willow’s awkwardness hiding steel underneath, Xander’s… let’s not talk about Xander. So much of what you like about Buffy the Vampire Slayer was there from the get-go; when Giles and Buffy clash in the first episode, it’s funny but there’s a hint of something more. There’s already a sense that she needs him to navigate this, and that she doesn’t have a choice because she’s linked to this other world of darkness, much as she would prefer to walk in the light.

Of course, there’s one counter-argument you could make: You could say that all this myth nonsense is well and good, but the show still looks terrible. It’s full of rubbery monster mask, sub-par fight scenes and production shortcomings they’ve tried to cover up with editing. The good stuff is good, but there’s also a lot of bad stuff, more bad stuff than in later seasons, so how can you say it’s just as good?!

Well, to answer that question, I need to tell you about another institution built atop the gates of hell: Darkplace Hospital.

Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace

Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace is an 80s low-budget monster-of-the-week horror show created by and starring author, dreamweaver and visionary Garth Marenghi… OR IS IT?

No, no it isn’t — Darkplace is actually a parody of cheesy 80s horror and action shows, created by Richard Ayoade and Matthew Holness. It’s a different take on the mockumentary format brought to prominence by The Office in 1999. Matthew Holness plays horror author Garth Marenghi, a self-obsessed and delusional parody version of Stephen King who, in the universe of the show, made a terrible TV show in the 1980s that never saw the light of day. Then, in 2004 they finally broadcast the show, interwoven with present-day interviews with the cast and crew, discussing what absolute visionaries they were back in the day, which is juxtaposed with the wonderfully terrible show that they made.

What makes Darkplace shine is the attention to detail; every aspect of the show lives and breathes "this was shot in somebody's garage\”. The intentionally bad sets, continuity errors, editing to cover up bad acting and sub-par special effects all make it a pitch-perfect send-up of cheesy old television shows. In the plot of the fake 80s show, Garth Marenghi plays Doctor Rick Daglass, a former warlock who opened a portal to hell under his hospital and who is now fighting back the demons and occult occurrences he’s unleashed, together with a rag-tag group of hospital employees.

All of that is funny, but it should get quickly – what keeps you interested is that in the same way that Buffy heightens real-world teen problems into the supernatural, each episode of Darkplace offers new insight into the warped mind of Garth himself. His twisted worldview is baked into the structure of the show, allowing each episode to explore some new, horrible aspect of his personality.

For example, he elevates his racism against Scottish people into the supernatural in The Scotch Mist and in Hell Hath Fury Garth elevates the real-world nightmare of “a woman you know being on her period” by turning Doctor Liz into a psychotic psychic who can make your head explode with a scream. Throughout it all, Garth writes himself to be the coolest dude ever; every episode ends with him standing atop Darkplace Hospital, gazing into the distance and brooding on a Boreanaz level while inner monologuing about what he’s learned. At its core, Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace is a character study of a delusional egomaniac, packaged as a parody.

But why am I telling you all this? Well, because watching Darkplace fills me with an unbridled joy. The cheesiness, the jank, the barely-held-together narratives, I find them all incredibly charming. It’s clear that the creators are very technically talented — because you have to be really good to make something look this bad — and that they have a deep love for the “cheesy” and “bad” media that they’re making fun of. I have that love as well, because this particular flavour of bad is often the result of humans being profoundly creative, and way more ambitious than what they’re able to pull off. It has the same charm as the action movie my older brother shot when he was, like, 14 years old, which, when I saw it, was a big part of me going “wait a minute, you can make movies?” And Buffy Season 1 fills you with the same energy and purpose — it makes you go “wait, you can tell stories like this?”

Usually, something made to be intentionally bad, like Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace, can never be as satisfying as the genuine article — but guess what, Buffy Season 1 is the genuine article. The biggest and most understandable criticism of Season 1 is that the production quality isn’t quite there yet and, as a result, the show is simply too cheesy. But I’m here to tell you: The cheese has matured.

I Robot, You Jane

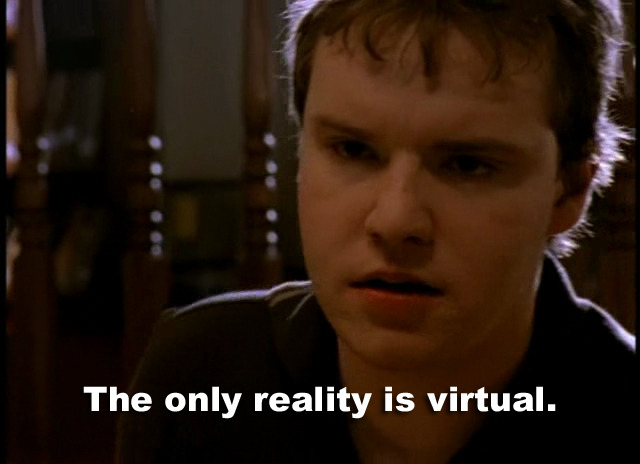

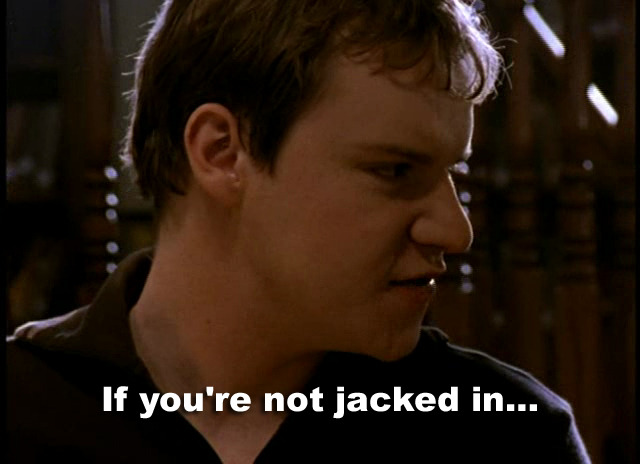

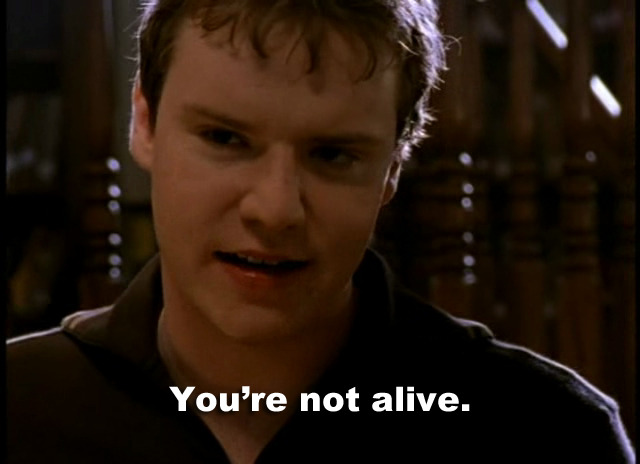

One of my favourite episodes of Buffy is one that often appears when people list their worst episodes; namely S01E08: I Robot, You Jane. The concept is absolutely bonkers and could pretty much be an episode of Darkplace. It starts with a demon getting trapped in a book in the 1400s, and the book winds up in Giles’ collection, which is being scanned and digitised as a project run by computer teacher Jenny Calendar. This means that the usually deserted library is invaded by a brigade of nerd students hopped up on cyberspace hype, much to Giles’ horror.

I want a tattoo of that whole speech.

Willow scans the book which releases the trapped demon onto the internet, and as a malevolent ghost in the machine, Moloch the demon poses as “Malcolm” a nice boy that Willow meets in an online chat room and quickly falls for. (This was back when the idea of meeting a potential romantic partner online was very strange, far from the standard that it is today.) Buffy and Xander are wigged out and try to investigate this Malcolm, only to be thwarted by the nerd brigade who are being mind controlled by Moloch. Nice nerd boy Dave tries to fight this mind control and his murder is staged as if he died by suicide.

Everything comes to a head as it turns out Moloch has taken over the minds of scientists at a computer research lab, where he’s having them build him a new body. He reveals his true nature to Willow, who understandably isn’t down with the whole mind-control and murder thing, and as per tradition Buffy gets to punch this problem in the face.

I love every part of this strange and ridiculous piece of television. From the corny fantasy/sci-fi mix to the on-the-nose commentary on online stranger danger. On the surface it’s goofy fun, and under the surface is a genuine core to the story that lets you get something out of it, even nearly 30 years later. Willow’s nerdy peers are mind-controlled by Moloch in a way that now feels very incel-coded; the more “jacked in” they are, the more susceptible they are to Moloch’s manipulation.

And there are the two great appeals of Buffy season 1; the surface silliness combined with the deeper, genuine core. Sure, maybe they were going for something more serious, we’re supposed to be thrilled by the fight scenes, not laughing at them and if you don’t see the appeal of I Robot, You Jane, I understand why Season 1 might be a bore. But if you enjoy the corny camp, the outright Garth Marenghi-style silliness, then Buffy Season 1 is a high, not a low.

The Problem with The Master

I have a few concessions to make before we wrap this up, starting with The Master. Let’s be honest, there’s no comparing The Master with Spike, or Glory, or even Adam. The Master is a completely impotent antagonist who’s trapped underground for the whole season and never really does anything. He exists as an idea of a looming, greater threat, which is fine, but it’s never going to be as interesting as an active antagonist that engages with the world. Even in the final fight he can only beat Buffy through some sort of mind control bullshit that I don’t think we even knew he could do? And then, once Buffy’s back from the dead, she handily dispatches in the epitome of underwhelming fight scenes.

The Master does manage to acquire “The Anointed One” but again that feels more like an idea than a well-executed concept. It’s the trope of the haunted creepy child, except all we get is an awkward-looking kid doing an impression of an emotionless vampire. They hype up his great purpose but all he ever does is show Buffy where to go in the finale, a task that any underling could have performed. To be fair, the writers fully realised this misstep and The Anointed One finally fills a function in early season 2 when Spike promptly murders him and we go whoa, this guy’s way cooler than The Master; he’s actually gonna do stuff.

I don’t want you to think that I’m blind to the imperfections of the season, but rather I think that those imperfections have, with time, become part of its charm. The swish-swoosh sound effects to mediocre acrobatics, the dramatic saccharine score, the low-key lighting used to hide all the things they couldn’t afford. If you look at the vampire dusting effect and compare it to later seasons, you’ll understand why they made the most of what they had at hand — like, crossfades.

Doesn’t it make you feel all cozy and nostalgic? I know I’m biassed because I actually did watch the show when it came out, though Teacher’s Pet scared me so much I had to step away for a number of episodes. But I enjoy Season 1 more now than I did 10-20 years ago, probably because you can’t see how wonderfully “of its time” a work of art is when you’re also of that time.

Conclusion

You’ve heard my arguments:

Firstly, a lot of what you like about Buffy was there from the get go, more than you’d expect.

Secondly, later seasons add more complexity, but they couldn’t have done so without the solid foundation that Season 1 lays down.

And thirdly, there are ways that the season is “bad” but those constitute a particular kind of cheese that has only matured over time. It’s enjoyable to me in the same way that a corny 80s movie is enjoyable; the technical faults have a charm that elevate the viewing experience. Later seasons may have higher production values, but they also have less cheese, and I enjoy both those things in different ways, meaning that they balance each other out and allow this technically inferior season to reach the same high levels.

I have one last caveat: None of what I said is true if you watch the HD remaster, which tragically crops away half the screen and fails to apply any of the same color correction, meaning that the moody dark atmosphere is completely swept away. Find the 4:3 DVD version and thank me later. And also, past self, please remember that it’s only 12 episodes. That’s not a slog.

You should watch it, and don’t skip any episodes. Not even the puppet one.

Jakob Burrows

Video published January, 2025

Text published March, 2025