The Real History of A Knight's Tale

A Knight's Tale is a cheerfully anachronistic medieval sports movie – it’s Rocky, with lances! It's an adventure, a romp, and a treasured part of my childhood. Forget about the grey and desaturated aestehtic that’s plagued historical films for the last two decades; back in 2001, A Knight's Tale dared to use a full palette of expression with vibrant music, colours and costumes, all intended to help a modern audience connect with an older story. It's upfront about being historically inaccurate, but the appeal of boldly anachronistic films is that, unlike your average Mel Gibson flick, they’re not trying to sneak stuff past you. You’ll finish Braveheart thinking that, yes, they wore blue face paint back then (which is incorrect) but no one’s walking away from A Knight's Tale thinking they actually danced to Bowie in medieval times. Films like A Knight's Tale tell you upfront what they are, they use all the tools they have to tell a compelling story, and they get you interested in learning about the actual history of the time.

And that is exactly what we’re doing today, using A Knight's Tale as a jumping off point to discuss: What was life actually like for a knight? Where does myth and reality diverge? What was the war raging in the background of this film - and who were the real people that lent their names to the characters? All this and more as we explore... The Real History of A Knight's Tale.

This is my longest video to date, and the longest blog post on this website (around 15,000 words), so if you want a more light-weight intro to the topic of medieval knights, check out my podcast Reel History, where we use historical movies and TV shows to learn about true historical events. Our episode on A Knight's Tale from 2021 was what inspired me to dig deeper into this topic!

Index

- Film Summary & Establishing the Year

- The 100 Years War

- The Battle of Poitiers

- Legacy of the 100 Years War

- The Origin of Knights

- How to Become a Knight

- Life as a Knight – At Home

- Life as a Knight - At War

- Chivalry & Romance

- Christianity

- Knightly Ideals

- Knights & Class

- Early Tournaments

- From Mêlée to Joust

- Ulrich von Lichtenstein

- The Black Prince

- Adhemar & The Free Companies

- Geoffrey Chaucer

- A Quick one on Wat Tyler

- Chaucer's Old Age

- Conclusion

Film Summary & Establishing the Year

The plot of A Knight's Tale revolves around William, a young squire whose knight passes away in the middle of a joust. William dons his master's armour and pretends to be him in order to finish the joust and get him and his fellow squires Roland and Wat the coin they need for food. After surviving the joust, William - who is from a poor background and who has always wanted to "change his stars" - convinces Roland and Wat to start a get-rich-quick scheme where William pretends to be a noble knight in order to compete in tournaments for prize money.

Through a classic training montage William levels up his knight game and the retinue goes on a romp around the "tournament circuit" in what's now France, expanding the crew to include gambling-addict and writer Geoffrey Chaucer and Kate, a brilliant blacksmith without whose help William would literally fall apart. Under the fake name of Sir Ulrich von Lichtenstein, William proves his mettle as a knight while falling in love with Jocelyn, a lady of noble birth, and thereby antagonising tournament champion Count Adhemar. Oh, and he also makes friends with the Edward, the Black Prince of England, who is ALSO hiding his true identity in order to compete.

Everything comes to a head at the "World Championships" in London where William inadvertently reveals his identity by visiting his father after a decade away. The jig is up and William is clamped in the stocks but the Black Prince decides to knight William, allowing him to compete under his own name. Sir William beats that baddie, kisses the girl, and we all live happily ever after. Even though it's the 1300s.

Now, the film doesn't give an exact year but we have a number of clues to work off, the most important being the reference to the Battle of Poitiers where the fictional Count Adhemar and the not-at-all fictional Black Prince are both present. This puts us in 1356, which lines up well with the fact that the pope is French, as we know from a joke in the film: “The pope may be French but Jesus is English!”

This line may seem like a throwaway joke, but it’s actually taken from a contemporary satirical verse: “Now is the Pope a Frenchman born And Christ an Englishman And the world shall see what the Pope can do More than his saviour can.” At this time, conflict between the papacy and the French crown resulted in 7 popes being based in Avignon, in what's now southern France, rather than Rome, and many an Englishman distrusted the fairness of these popes, who seemed to be under French control. This is just one of many details showing how A Knight's Tale is a much more thoughtful film than it might seem.

The only thing that conflicts with the 1356 date is that behind the scenes they talk about taking influence from the 1970s because the film is supposedly set in the 1370s. Hence all the Queen and Bowie, and costume designs that took inspiration from the Rolling Stones 1972 tour. But the film is not too concerned with historical specifics and this “1370s” claim might be more of a vibe than a specific date. Regardless of the specific year, we’re in the mid 1300s which, in this time period, in this area, means one thing: You’re in the middle of the 100 Years War.

The 100 Years War

This is a war with excellent branding I have to say – it sounds like something out of a fantasy novel; how could one war even go on for that long? Well, the truth is that it didn’t, really, as this wasn’t one continuous war. There were breakouts of hostilities and invasions, interspersed with periods of relative peace, but looking back we’ve grouped these together as one war with multiple phases.

It’s a war between England and France, though of course these were not the countries we know today geographically or culturally. The population in England may have spoken Old English but the language of the court was French because in many ways the English ruling class was French. This was hundreds of years after William the Conqueror, the French-speaking Duke of Normandy, came to what’s now England and installed himself as king, so you’d be forgiven for thinking that the invaders might have taken up the local language in those intervening centuries. But William the Conqueror, as per the name, was not coming over to assimilate into the existing Anglo-Saxon culture; he was imposing new norms, establishing the feudal system and redistributing lands from opposing English nobles and clergy to his own French-speaking Norman followers. But the ruling class across what’s now England and France didn’t just speak the same language; a lot of them were actually family as well. There was a patchwork of intermarriage, alliances and overlapping claims of land, making this war more of a family feud, really, than an international matter as we’d know it today. It was through this century of conflict that the national identities of England and France started to form because, after all, a common enemy helps us identify ourselves by what we are not. And that is why, by the end of the 100 Years War, the English nobles spoke English.

The catalyst for the 100 Years War was the death of Charles IV of France in 1328, more specifically the fact that he had no direct heir, sparking a succession crisis where two claimants emerged: a cousin of the dead king, who became Philip VI of Valois, and Edward III of England, who was the nephew of the dead king through his mother, Isabella of France. Now, Isabella deserves a whole video of her own, but I swear I’m trying to keep this as concise as I can so the short version of her story is that only a year earlier Isabella and her presumed lover Roger Mortimer led a rebellion, deposed Edward II and most likely had him killed before installing Isabella’s teenage son on the throne. Something they possibly regretted a few years later, as Edward III had Mortimer executed. Regardless, in 1328 the French nobility recognised Philip VI as king, a decision that Edward III later contested, claiming the French crown for himself.

Realistically Edward III wasn’t necessarily looking to take over all of what’s now France; his focus would have been on the areas of continental Europe that had been in and out of English control for several hundred years. At this time, these areas were held by England but as vassal states of the French crown; a bit of a contradiction since kings don’t want to owe allegiance to other kings unless they really have to. Any English lords installed to rule over these lands could end up with split loyalties and any local lords, should they disagree with the English king, could appeal to the French king who would then summon the English king to their court to resolve any disputes; all in all, an untenable situation as far as the English royals were concerned. This mess had been temporarily fixed by the former English king (Edward II) sending his son to act as a vassal to the French king, while not doing so directly himself - but now, that son who was sent over was king himself, and he thought he had a better claim on the French crown, so he was not going to continue that subservient charade.

What followed was a decade of escalating tensions and diplomatic manoeuvring as Edward sought alliances with European powers to counter French influence while Philip consolidated his power within France. Disputes over taxation and control eventually boiled over and in 1337, Philip confiscated Aquitaine, citing alleged breaches of feudal obligations and Edward’s harbouring of one of Philip’s enemies, leading to the start of the war.

The first years of the war saw a naval campaign by the English alongside French landings in towns on England’s east and south coast. One major engagement from these early years was the Battle of Sluys, fought on June 24th, 1340. This was off the coast of Flanders where the English navy decisively defeated a larger French fleet which, for a time, established English supremacy over the channel and prevented a full-scale invasion of England. It was said that after this battle, the fish drank so much French blood that if God had given them the power of speech, they would have spoken French.

In 1346, Edward III invaded France and on August 26th, the English army, heavily outnumbered but well-trained and equipped, confronted the French army at the Battle of Crécy. English archers, using the longbow to devastating effect, played a crucial role in this English victory - as becomes a theme throughout the 100 Year War.

The Battle of Poitiers

Before I get carried away here – this is not a video on military history. There are many fine creators online sharing their deep knowledge on this topic and I would urge you to seek them out if you want to learn more about the blow-by-blow developments of this extended conflict. However, you cannot understand the Europe that A Knight's Tale takes place in, without a basic grasp on this war, which would come to change the role that a knight plays in society. Before we move on to the average life of a knight in this age, there’s one war-related point we’d be remiss not to mention: The Battle of Poitiers.

This battle is an actual plot point in the film, not so much because we see it but rather because it leads to Adhemar disappearing from the the tournament circuit. The two rivals of the film are both craving a confrontation, with William stating that he’s not really champion until he’s bested Ademar, and with Ademar off fighting the war, getting increasingly frustrated with reports of “Sir Ulrich” winning tourney after tourney in his absence. So why was Ademar called away at this particular point?

Well, it’s 1356, and at this stage of the war, Edward the Black Prince was in his mid-twenties, marching through French territories, looting and pillaging along the way. The French, meanwhile, have a new king, as Philip VI died after 22 years of reign and it’s his son, John II, who leads the French against the English at Poitiers. The French had a much larger force but the English army was well prepared and positioned, so when the French cavalry charged, English longbowmen on higher ground were able to unleash a barrage of arrows, causing chaos and confusion and allowing the English infantry to hold their ground. This was another battle that demonstrated the effectiveness of English longbows and the importance of strategic positioning in medieval warfare. Despite the advantage in numbers, the French suffered heavy casualties and eventually broke ranks, retreating.

This was a resounding victory for the English, especially because King John II of France was captured during the battle, along with many of his nobles. John II was held captive for four years in several locations, including the Tower of London and England and France eventually did negotiated his release in the 1360 Treaty of Brétigny, though when this particular boy was back in town, he faced a lot of unrest and dissatisfaction among both nobles and the general public as the treaty ceded significant territories to England on top of a massive ransom. For England, this was the peak of their dominance during the period - the lands they held on the continent were officially no longer vassal territories of France, making the Duchy of Aquitaine, Bordeaux, Gascony, all fully English. In addition, France surrendered Calais, a strategic port city on the English Channel, which would remain in English control until the mid-16th century, as well as additional territories in the north (Ponthieu and Guînes). So you could see why John II’s return wasn’t met with great excitement in France, which had dissolved into near anarchy in his absence, never mind his enormous ransom that the people had to pay. John II would die just a few years later, having voluntarily returned to England, if you can believe it, but the war would go on, and the tide would turn, and turn again.

Legacy of the 100 Years War

One of my sources is Gordon Corrigan’s “A Great and Glorious Adventure” and I do enjoy the brevity Corrigan manages to bring to this enormous topic but it should be said that this is tinged with a lot of English patriotism. Corrigan expresses pride in these events and overall comes off as what we in Ireland might call “a bit of a Brit”. I suppose I can’t fault him for it, some of the military achievements are impressive, but I do find it interesting how much this time period lives with us to this day. In many ways, this conflict is the foundation for French and English nationalism, and the reason they hate each other.

When Charles de Gaulle was president of France, he had a standing order that while travelling around the country he was never to be within thirty kilometres of Agincourt, the site of a later French defeat. This was 500 years after the fact. And on the other side of the channel, the English claim on the crown of France was only lifted in 1801 and only because the French Republic had been established and England wanted to stop this whole “revolution” thing from spreading. It’s why, for centuries, fleurs-de-lys, symbolising France, featured heavily on England’s coat of arms. This period marked a transition from a fully feudal system to a sort of proto-nation state, making this a fascinating period of development – especially for those who held the rank of knight.

The Origin of Knights

At the time of A Knight's Tale, knights had all manner of customs, rituals and pomp, but to properly understand these mounted warriors, we'll need to rewind to a time before any of this was formalised, a time where “knights” didn't really exist.

In the Roman Empire there was the upper class, patricians, and the lower class, plebeians. However, any citizen who could afford armour, could join the army, which had both patricians and plebs in its ranks. And if you could afford a horse alongside armour and weapons, you could become part of the equestrian class. The property requirement was less than that of the senatorial order, so these were men of significant wealth, but not necessarily of noble birth. They were called Equites, cavalrymen, and today, in English, they’re sometimes referred to as knights. They had the right to distinctive attire, titles, reserved seating at public events and, like medieval knights, they often subscribed to an ethos of heroism and glory. To be clear, these are not the medieval knights of A Knight’s Tale, they differ in many ways – one being that their rank could be passed down hereditarily - but they did set the precedent of a distinct class for mounted warriors, with special privileges and duties.

Several centuries after this, and still centuries before A Knight's Tale, Charlemagne was picking up the pieces of the collapsed western Roman Empire and forging it into his Frankish Empire that included modern-day France, parts of Germany, bits of Holland, bit of Italy – basically it was big, larger than any one realm in Europe for centuries, meaning that Charlemagne needed mobility. So he recruited people wealthy enough to own horses, and re-established this concept of knights. It should be said that these are proto-knights, still a long way off from the fancy knights who played on tournament grounds, but Charlemagne did set up several important concepts. The deal was - agree to serve in his imperial army as a cavalryman, and as a reward you got a benefice, an allotment of land, essentially making you a lord. This was the beginnings of fiefdoms and feudalism as we know it; with an overlord or king assigning parcels of land to individuals who are responsible for running that land, farming it, and producing the wealth – and then paying taxes to their overlord but keeping a good chunk for themselves.

So the medieval knights we know developed from this. They were typically sons, nephews and relatives of noblemen within the feudal system; and indeed, being a noble and being a knight became more or less synonymous for a time. Of course, you could also go into the clergy, and the increasing need for able administrators that meant not every noble had to be a silly boy with a horse and a stick. Common people could occasionally become knights but it was not a usual practice.

But what was life as a knight like, and how did you become one to begin with?

How to Become a Knight

While the down-on-his luck Sir Ector was happy to take on a poor common boy, William really failed at the first step of becoming a knight, which is to be born right; technically you could find yourself a wealthy patron, but usually your family would be part of some kind of nobility. Your father could be a knight but he didn’t have to be, since being a knight isn’t hereditary, it’s something you work to become. The popular form of inheritance was primogeniture, meaning that the first born boy got pretty much everything, so knighthood was a popular path for second sons and beyond since knights enjoyed a great degree of social mobility and could, based on their deeds, rise higher even than their elder siblings.

As a prospective knight, you’d stay in your family home until about the age of 7, probably with female relatives tending to your needs and education; after that you’d be sent to another noble’s household (often a relative) to work as a page. Pages were servants of lords and knights who ran messages, cleaned, served at meals, and this wasn’t seen as demeaning because it was part of your education – you’re learning the ways of the household and in exchange you’ll usually get some basic combat training alongside other skills deemed important to the nobility; like reading and writing, swimming, dancing, courtly manners, and, of course, how to shred on that lute.

Around the age of 14 a page could graduate into the position of squire, making you, in effect, a knight in training. The word squire is derived from a Late Latin word meaning “shield bearer” and that’s exactly what you did; tended to your knight’s supplies, banner, armour, and you would be training with real weapons and armour, not the practice swords of your youth. Squires would travel with their knights and could see a fair share of combat, though their main role would be getting their knight in and out of armour rather than participating themselves.

After another 7 years, around the age of 21, you would be eligible to become a fully fledged knight. The ceremony of creating a knight varied over the centuries and could be more opulent if the knight’s lord was rich, or more religious if the knight’s lord was pious. One thing that remained constant was that knights created other knights. The church did try to worm their way in there, in the same way they controlled ceremonies like marriage and coronations, but knights held fast to their tradition.

The evening before the “dubbing” ceremony, the squire might spend time in vigil in a chapel and/or they could start the day with a bath, both activities designed to cleanse the soul in preparation. Depending on the budget there may be lavish clothes to dress in and extravagant gifts, though for poorer knights this was often limited to just a single new cloak, a symbol of the knight’s new status. Often there was an element of public witness, because ceremonies like this held an integral role within the communal structure of medieval life.

The act of “dubbing” seems to be one of the few universal features, though what dubbing meant changed over time. It comes from a French word meaning “to arm” (“adouber”) and at its core it involved the knight receiving his belt and sword. This may be followed by the “collée”, or accolade, a ritual blow to the body, which could range from a light tap on the shoulder to a forceful cuff of the head. There are arguments over the origins of this; it could have been to help the knight remember their oath, or to symbolise the last blow you ever receive without retaliation. Either way, it’s very similar to what I did to my podcast co-hosts the day we started our history podcast. I smacked them with two microphones, and said LET THIS BE THE LAST TIME THESE MICROPHONES PEAK.

In the 1200s this accolade developed into tapping the flat of a sword blade to the shoulder of a new knight – the image we now think of as dubbing, and the one still performed in England today. Knights would often be dubbed on the eve of a battle. Under English custom there was a special title of “knighthood banneret” which could only be awarded on the field of battle and only in the presence of the king, or at the very least, the king’s standard. Normally knights were entitled to triangular pennons, but these knights were allowed rectangular bannarets and their own coat of arms or heraldic device. While these bannaret knights could set up their own households and have knights serving them, the first career step for most young knights would be to ingratiate yourself to some lord, often the very person who knighted you. Being a knight made you upwardly mobile in society, but it was also a big gamble, because it was extremely expensive and you only got what you wanted if you could prove your worth.

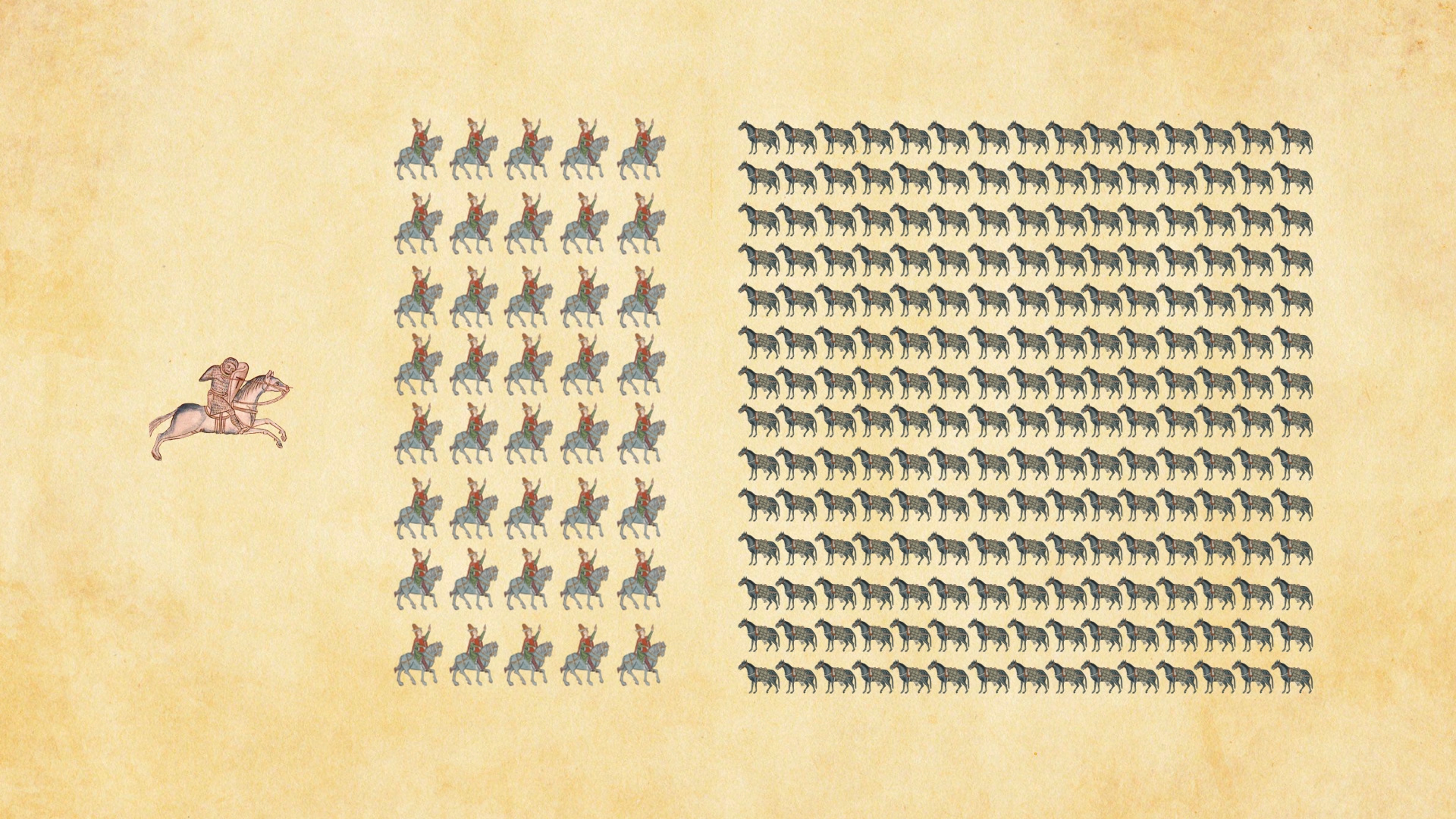

Life as a Knight – At Home

A knight without an income from either their family or their lord would quickly run out of money. Knights were expected to provide their own equipment and multiple horses - often they’d have one for war (called a destrier), one for riding outside of battle (palfrey) and a packhorse for equipment (sumpter). Not all horses are created equal and for the average price of one warhorse in the 1160s could be equivalent to 40 riding horses or 200 packhorses – or 4,500 sheep, if you prefer. That’s four or five times what the average knight might live off in a year.

Whether travelling for war, tournaments or diplomacy, each knight was expected to have a retinue, with a page or squire to look after their armour, a groom to look after their horse and, often manservant to look after the man himself. Of course, you were responsible for making sure your retinue got paid and the most common way of doing that was to join a richer lord’s retinue yourself. A lord’s household armed retinue, or mesnie, made up a trusted set of knightly bodyguards who became like family - in some cases they were literally family but often not. Attaching yourself to a lord as part of his retinue was a great way to advance, as you’d have the lord’s ear to nag for favour and lands, which the lord was expected to deliver. The size of his retinue, therefore, was determined by the lord’s ability to give and a large retinue of knights was an obvious display of power, which, in cutthroat times, could be necessary to retain that power. In other words, size mattered when it came to retinues, and nobles would surround themselves with tens or even hundreds of knights, all vying to be the favourite, because being the favourite meant land.

If you were given stewardship of a parcel of land you would become quite wealthy if you weren’t already and in return you’d swear to serve the lord for a given period of days in a year – but you’re only bound for that specific period of time, and if this sounds like a good deal, just you wait, it gets better, because the number of committed days of service was usually 40. So you only had to be on active duty 40 days in a year, and could spend the rest of your time managing your land, getting bored and getting into sports like jousting.

Now you might be wondering, how could this be the case when some wars famously lasted longer than 40 days. Well, while knights formed the cavalry core of the feudal medieval army, they rarely died in battle for several of reasons. Firstly, battles were generally avoided unless you had overwhelming numbers, so you’d be more likely to spend your time ravaging the countryside of your enemy, or sitting around waiting during a siege. Secondly, if there was a battle, you as a knight had the best armour, making you a bit of an un-killable Robocop, and even if you did lose, your enemy was likely to let you live and hold you for ransom. This was a key way for knights to earn money in times of war so the death of an enemy knight could be extremely annoying. (Never mind the peasants dying in the muck.) So in practice, knights would often serve more than 40 days depending on how successful the campaign was, because if you’re doing well in the looting of whatever country or region you’re in, why would you want to leave?

Of course, knights didn’t spend all their time fighting. A lot of time would be spent in their lord’s great hall, which served as the hub of any aristocratic community. This is where, each day, a meal would be shared - paid for by the lord. Mutton, pork, chicken, beef and fish would make regular appearances at these meals, seasoned with sage, garlic, and mustard. You’d also have mainstays like rough-ground bread, eggs, cheese, peas and beans and ale, though wine was popular in more affluent circles. As for dress, fashion obviously changed during the medieval era but commonly knights and nobles would wear stockings or hose, fashioned from silk or wool, alongside a shirt worn under a tunic. They’d have a coat to wear outdoors along with a mantle or cloak. Over time, it became increasingly popular for lords and families to use distinctive colour schemes in public, a sort of uniform adopted by the retinue.

The dinner in a lord’s hall could be a crowded affair with dogs, birds of prey or even horses welcome - though according to the first ever English book on etiquette, you should refrain from mounting your horse in the hall. The Book of the Civilized Man by Daniel of Beccles gives us a view into proper behaviour at the time, for example you should avoiding urination in the dining hall (unless you’re the host) and you should look to the ceiling if you need to belch. It also held advise about keeping your cards close to your chest, suggesting that you should speak little when eating at the table of the rich, or even “If there is something you do not want people to know, do not tell it to your wife.” Other parts of this book you might recognise from what’s still considered “proper decorum” in many cultures today – such as don’t speak with your mouth full, don’t put your elbows on the table, and don’t pick your teeth or nose.

These rules for proper behaviour got more strict the higher up in society you went; a king’s court would be luxurious but also dangerous for a knight, with skills of intrigue and gossip often playing a more important role than martial prowess. It was very important to control your temperament, as a display of anger could discredit someone as “unbalanced”. As a knight at court, you might therefore have to endure the goading of your enemies while retaining an icy façade. Back in a lower lord’s hall this might be less of a problem but one thing remains the same; no matter where you’re at as a knight, you’re always trying to advance your position by gaining the favour of your lord. And let’s be honest, if you’re a knight, the best way to curry favour with your lord is through war.

Life as a Knight - At War

Knights were brought up with lots of martial training – but they’d be used to fighting as individuals – so in times of war it could be difficult to get them to act as a team. Indeed, people of the “nobility” often didn’t consider themselves under the command of anyone in particular; they might show up as part of their feudal obligation, but beyond that you may need to consult with them and pander to them in degrees relative to their station to get them to actually do what you want. Under the feudal system, nobles and common folk alike served out of obligation, which can be fleeting, or at least limited — note that the 40 day limit also applied to common folk, who understandably wanted to be home to plant and harvest their crops. This was part of what led to an increasing professionalization of the English, and later French armies during the 100 Years War. Once the English started paying their soldiers, it was a lot easier to order them around and to hold onto their loyalty for as long as there was coin. The English were ahead on this development and Edward I, in the first decade of the 1300s, was paying everyone in the army except those at the very top (who we might call generals).

In the earlier medieval period, army tactics relied on well-armoured heavy cavalry who were able to ride through infantry lines with relative ease. This matched the contemporary understanding of the social order; knights probably believed it natural that they could smash through lesser men. However, in reality this had more to do with the infantry’s poor equipment, poor training and poor positioning.

You might recall how Mel Gibson and his painted Scotsmen in Braveheart defeat the English cavalry through the inventive use of pointy sticks. I remember watching that and thinking “oh, yeah, sure, no one has ever thought of sharpening long sticks or digging ditches before,” but there is some truth to it. At the battle of Bannockburn in 1314, Robert the Bruce’s well-organised infantry were able to hold against the normally destructive English cavalry charge, contributing to a decisive Scottish victory. The English took the lesson to heart and deployed it with great results against the French (and also against the Scottish). Paying the army instead of pulling unwilling farmers from their fields allowed the infantry to be well-trained and tactically deployed, turning the tables on the nobles, and allowing English longbowmen to rain down destruction on their French “betters” in battle after battle. After all, if you have 5,000 competent archers firing every 6 seconds, that’s 25,000 arrows in half a minute. If you put those archers in the right place, it doesn’t really matter who your daddy is; you and your horse are both going down (Agincourt numbers).

As focus shifted from cavalry to infantry, the role of the knight developed. Instead of always being part of heavy cavalry, they would fight on foot as men-at-arms. Not all men-at-arms were knights, perhaps one in five, but you’d see a lot of aspiring knights in this group. This was an infantry much better protected than the common folk of past wars; with English men-at-arms wearing mostly chainmail, while their French counterparts wore plate armour. These men-at-arms still had horses, but they were used for transport rather than battle, and of course the horses were essential for the chevauchée, a key component of medieval warfare. A chevauchée is a destructive horse raid where mounted knights conduct various atrocities in enemy territory, destroying crops and settlements before moving on at a fast pace. Quick wins are taken, well-garrisoned forts are ignored, and overall the common people suffer every imaginable horrible fate. Think of the Uruk-hai ransacking Rohan and you’ll have an idea of what these “honourable” knights were up to – except they were on horses so these children certainly wouldn’t have gotten away. It was sadistic and horrible work, which seems to have mattered little to the nobles that carried it out because to them it was an opportunity to loot. And to the wider war effort, it was a way of stripping resources from your enemy - because if the poor can’t reap their harvest, they can’t pay rent to their lord.

Another essential part of medieval warfare was the siege. Just as power was centralised in the upper classes, strongholds were created to safeguard and centralise control over a territory. Most towns or cities were fortified in some way, and disputed regions could end up with numerous forts. The taking of these could involve siege-engines like you usually see in the movies but equally important was the struggle under the surface, as specialised minors would be set tunnelling under the walls. This usually wasn’t to tunnel in, Great Escape style, but rather to create tunnels that you could then collapse by burning the wooden supports, thereby collapsing the wall of the keep above. Often the besiegers would strike a deal with the besieged along the lines of, if no one comes to save your bacon by a certain date, you’ll give up the castle. If the besieged would agree to no such deal, they could face horrific consequences if and when the walls breached.

To quote from Thomas Asbridge’s “The Greatest Knight”:

While knights could still be part of feudal household retinues, these lost some importance over the course of the 100 Years War, and instead there was a rise in indentured retinues. Anyone of banneret rank or above, in England, could employ knights or esquires via contract, sometimes for a set time period, sometimes for the lord’s entire life. These contracts specified wages, expenses and the type of service to be provided (for example, only within the country or also abroad). Members of an indentured retinue would wear their lord’s badge or uniform and a portion of any ransom or plunder they took would usually go to the lord. This method of contracting knights was sometimes referred to as “bastard feudalism”, not because we had a bunch of Jon Snows running around, but rather because it departed from traditional feudalism with its system of vassals. It allowed knights to be mercenaries without calling them mercenaries.

Regardless, there was still this interesting balance between obligation and privilege; the English government enacted regulations to persuade those with lands worth 40 pound or more a year to accept a knighthood. Which sounds a bit weird - I mean, if you had to go to war, being a knight didn’t hurt, it doubled your pay and if you got into a sticky situation you were likely to be held for ransom rather than killed outright. In fact, transporting and managing captives during a campaign was impractical so sometimes enemy knights would be released on the promise that they would pay their own ransom later - a promise that was often kept but sometimes not. But regardless of these benefits, being a knight was so expensive that some Englishmen actually turned down knighthood – and they were fined for it.

Remember, this was a time where crowns traded hands through warfare as often as succession, so the king was usually a usurper from someone’s point of view. Popular kings therefore might be likely to see people sign up as knights while unpopular ones could be busy trying not to get smothered to death in the Tower of London.

Chivalry & Romance

Let’s talk about chivalry. Was there a really code of conduct for knights and, if so, did they adhere to it? Well, the first thing to note is that chivalry is subjective. If you look at the root of the word it just means to “act like a knight” and there’s no one written law for what it means to be a good knight, it wasn’t that formal. Generally the number one rule is to do whatever your liege lord appreciates, as he’s the one to decide who advances in society. If your lord appreciated ruthlessness from his knights, then forget about any of that soft hearted writing poetry stuff, that’s not going to get you anywhere.

The idea of the honourable and “chivalrous” knight is largely a literary idea, one that existed and was very popular at the time of A Knight's Tale. Just like today, the sense people in the middle ages had of what a knight should be was informed not just by real history, but also by fantasy. During the 1130s, the monk Geoffrey of Monmouth spun up a popular, semi-mythical pseudo-historical past with his “History of the Kings of Britain”, featuring someone you might have heard of: King Arthur. The lacking connection to reality didn’t stop Monmouth’s writing from becoming massively successful and, unlike the 2004 Clive Owen/Keira Knightley vehicle, it created an obsession with King Arthur and his knights and laid the foundation for Arthurian myth. But just because a society tells itself stories about heroes, that doesn’t mean that those heroes are realistic or that they reflect a contemporary truth, just look at the Marvel Cinematic Universe and compare it to your own lived experience today.

These popular stories also contained a lot of romance, specifically in the genre of courtly love which usually themes of infidelity. To knights, noble women were primarily conveyors of property and breeders of children - they were used to expand your lands and to establish your dynasty. Marriage, therefore, was not a thing of romance, so stories of courtly love tended instead to focus on love between a knight and another man’s wife. It sounds strange but this was considered to be a more pure form of love since it could bring no material benefit to the knight. This type of love supposedly improved the man; if he pined after a woman he would do everything to impress her, from simple things like keeping his teeth to more grand ideas of embodying valour and honour. The steps of the romance would start with love at first sight and wind through passionate declarations (which the virtuous lady would reject), and heroic deeds that won the lady’s heart, before a secret consummation, and a tragic climax. Of course, this doesn’t quite add up with the fact that adultery was a crime as well as a sin but these were meant to be titillating stories, not reality.

Not that we need it, knowing human nature, but we do have records of knights being willing to swear whatever oath they might need to, to get into a lady’s garments. Geoffroy IV de la Tour Landry wrote “The Book of the Knight of the Tower” as a guide for his daughters on how to avoid smooth-talking men at court. He described a situation where three ladies exchanged opinions on their lovers, only to find that they shared a favourite who had told each of them that he loved her best. They confronted him and he was in no way ashamed, saying “For at that time I spake with each of you, I loved her best that I spake with and thought truly the same”.

Stories of courtly love were a romantic ideal, not meant to be emulated directly. But that seems to be exactly what Jocelyn and William do. The 12th century French poem "Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart” introduces the love story between Lancelot and Guinevere, King Arthur’s queen, and in it Guinevere asks Lancelot to lose a tournament to prove his love, something that director Brian Helgeland decided to incorporate into his story. Just like in the film, Guinevere changes her mind, instructing Lancelot to win instead. It makes sense that Jocelyn and William would emulate the love story of Lancelot and Guinevere, which was popular at the time, - our lady is doing the equivalent of asking Will to hold up a boom box in the rain because she saw it in a film.

Christianity

Christianity was another main influence on what was thought to be “chivalrous” as the religion intwined itself with concepts of knighthood over time. In a medieval Christian society, the idea of reward or punishment after death wasn’t some abstract notion; it was actively feared, and while “Thou shalt not kill” isn’t the top commandment, knights would still grapple with the contradiction that their behaviour could end in eternal damnation. The church meanwhile was understandably concerned about the disorder and violence caused by mounted warriors roaming around Europe. Even in times of peace between kings, neighbouring lords would squabble with one another and conduct “private wars” where they decimated one another’s sources of revenue. And by “sources of revenue” I mean people, they would murder each others peasants indiscriminately. I mean these people were absolute bastards, and I suspect Pope Urban II would agree. In 1095, he came up with a nifty solution aimed at minimising violence… in Europe.

He started a holy war.

It was by no means a foregone conclusion that people would answer when the pope called upon good Christian people to recover the sacred city of Jerusalem from Islam – but answer, they most certainly did, in large part because the pope proclaimed that participating in the expedition would cleanse the soul of sin. Knights were therefore able to ply their trade of warfare with the sanction of the church and this was a powerful incentive that affected the development of knights moving forward, including the creation of knightly orders dedicated to Christian ideals such as the Knights Templar, who combined the warrior life with something more akin to monkhood. (Paladins, if you’re into D&D). The taking of Jerusalem in 1099 was a near-miraculous victory that would inspire generations of knights to participate in bloody crusades of their own.

It should be said that while religion was part of the fabric of society, everyone wasn’t necessarily a pious believer. One bishop complained that when rulers were in mass, they took the opportunity to hold audience at the same time, getting a bit of work done - and while you were supposed to partake in communion and confession every week, the average was probably closer to a few times a year, with Easter being the only fixed date. It was at the very end of life that people invariably became pious, paying for people to pray in perpetuity on behalf of their souls, and often giving a lot of their riches to convents, chapels and pilgrimages instead of to their families.

Knightly Ideals

A knight’s devotion to any Christian ideals could certainly vary, but one constant among knights was the respect for your word and the honour of your oath. Once you’d sworn an oath it was very much frowned upon to betray it – I mean, people obviously did, but it was seen as a treason against knighthood itself. Please note, though, that treachery and lying was absolutely fine as long as no oaths were broken. As Barbara Tuchman observed in A Distant Mirror: “When a party of armed knights gained entrance to a walled town by declaring themselves allies and then proceeded to slaughter the defenders, chivalry was evidently not violated, no oath having been made to the burghers.”

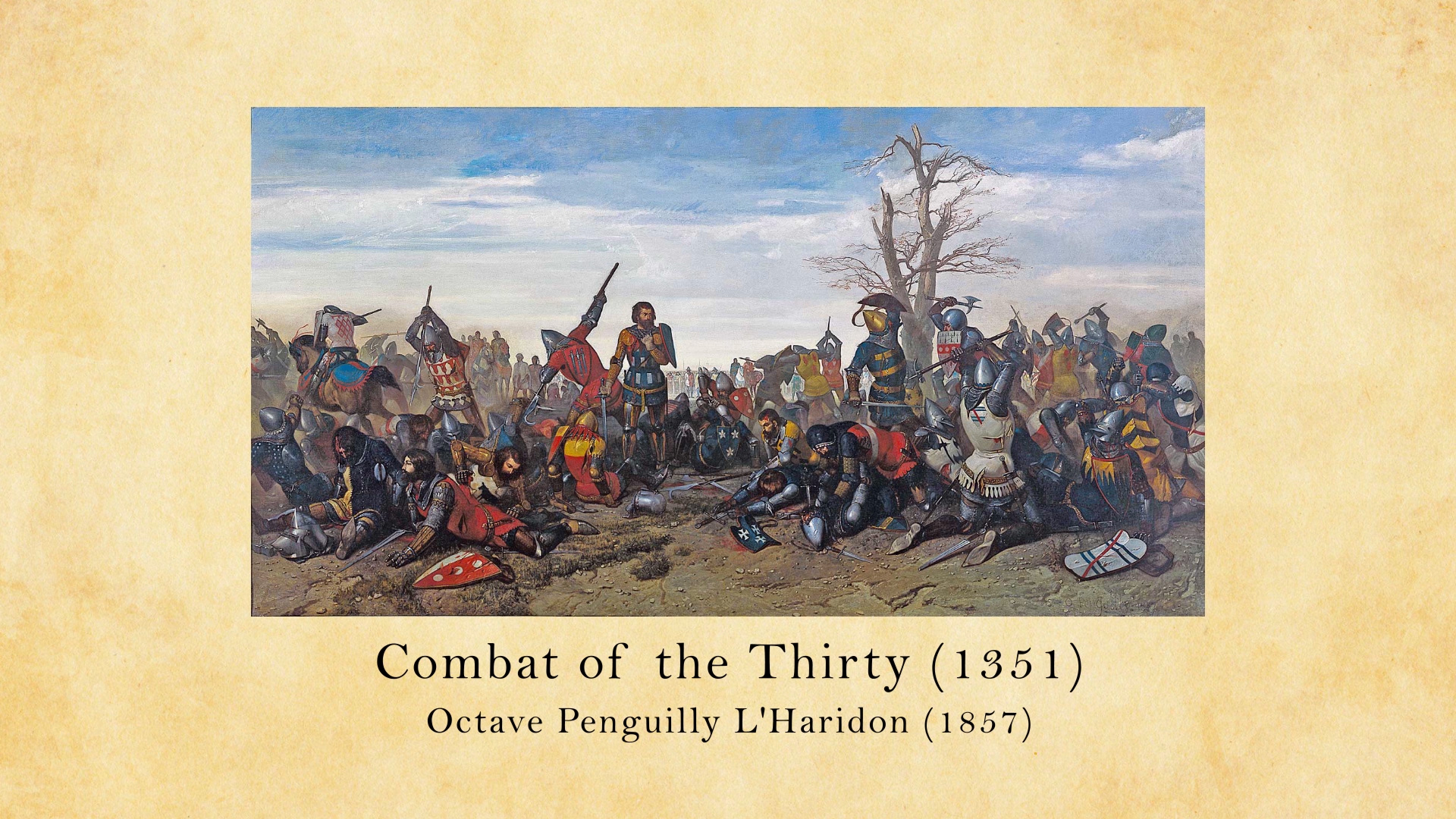

You can probably tell that chivalry is a bit of an amorphous concept, but we can get a firmer grasp on what was considered chivalrous by looking at what was generally lauded and praised among knights, such as the 1351 Combat of the Thirty. Now, we’re all familiar with the trope where, on the eve of battle, you make the offer of single combat instead. This didn’t happen as often as its portrayed in films; and if an offer like this was actually made it was often a sort of taunt rather than a serious possibility. But during conflict in Brittany, one French noble challenged his Anglo-Breton counterpart, and when their retinues insisted on joining, they agreed to hold a combat with thirty on each side. This had the formality of a duel, with terms agreed and courtesies exchanged - and they even had a recess to catch their breath in the middle of battle, after a few people had died. During this break in fighting, one of the lords called out for a drink, and the other responded “Drink thy blood […] and thy thirst will pass!”

The Combat of the Thirty only ended when all were injured and one of these nobles lay dead, along with eight of his party. While some viewed this event as a great waste, it was lauded far and wide and survivors who participated would find themselves given great honours. It seems strange that this formal mass duel happened while armies were getting more professional and nobles were mowed down by the arrows of common men – but it shows how nostalgic ideals of chivalry were very much alive in the hearts of medieval men.

If you Google “chivalry” you’ll find no shortage of crispy jpegs that claim to formalise the rules of chivalry. But these often reflect a modern idea that has more to do with the Romantic movement of the 1800s than the actual medieval period. During the 1800s people were very eager to dig up and dust off old stories and archetypes that would help them form a solid national identity. It was a time of idealism, patriotism and romanticising the past. For example, there was a big Viking-craze in Nordic/Germanic countries during the 1800s, and it’s where a lot of modern misconceptions around Vikings would have developed, such as the whole “horns on helmets” thing. Similarly, stories of knights and chivalry were popular in this Romantic movement and it’s where we see the modern idea of chivalry emerging; opening doors for women, acting like “a gentleman”, etc. And though Europe in the 1800s allowed for more social mobility than medieval times, this modern concept of chivalry, just like the courtly manners of actual knights, did serve as a way of distinguishing and separating the wealthy from the poor. It’s not surprising that class divisions survive to this day given how deeply ingrained this thinking is.

Knights & Class

A Knight's Tale does a good job of portraying the classist element that existed in feudal society. It makes sense that William would have to assume the identity of someone in a higher class, and that he would have trouble doing so as he lacks the etiquette, context and understanding of how the upper class talks, behaves – and even thinks. Throughout the film he learns these refined ways, engaging in courtly love, dancing and, of course, developing his natural talent talent for jousting. One could either see this as a savage commoner becoming refined, or we can see how the oppressive class system was holding him back from achieving his full potential, justifying the use of subterfuge to break down those class barriers.

There was actually a degree of class mobility in medieval Europe. About half of all noble families would disappear into obscurity over the course a century, either through failing to produce a male heir or by sinking into the lower classes, and new noble families would rise to take their place. And as Barbara Tuchman writes:

Sumptuary laws were put in place to prevent people of lower class from getting too fancy. For example, peasants might be forbidden from wearing any colour other than black or brown. Bourgeois traders could be forbidden from owning a carriage or wearing ermine. Different ranks and income levels were given limitations on how lavishly they were allowed to present themselves, how many minstrels they might have at a wedding. In an English law of 1363, a merchant worth £200 was entitled to the same clothes and food as a knight worth £100… so you could bend the rules if you had enough cash. But in general these barriers were meant to keep common people in check, just as barriers have always pushed down on oppressed people to allow the hoarding of riches and comfort for the privileged few. And yet we have always spun stories of “rags to riches” underdogs, a sort of “it can happen to you too” lie that keeps people in check and prevents us from properly challenging the status quo. You’ll note that the film doesn’t end with “commoners can participate in tournaments now because William has proven that commoners are just as able,” but rather William is allowed to enter the upper echelons while everyone else should do well to stay put where they are.

Instead of showing the system as inherently broken, with nobles like count Ademar making life tough for commoners across the world, the feudal system is overall shown to be okay – Adhemar may be a bad egg, but at the top of the order is a decent person (in the Black Prince), so things aren’t so bad really. But I suppose wishing for a total reorganisation of society would be both historically inaccurate and too much to ask of a film that is primarily concerned with tournaments.

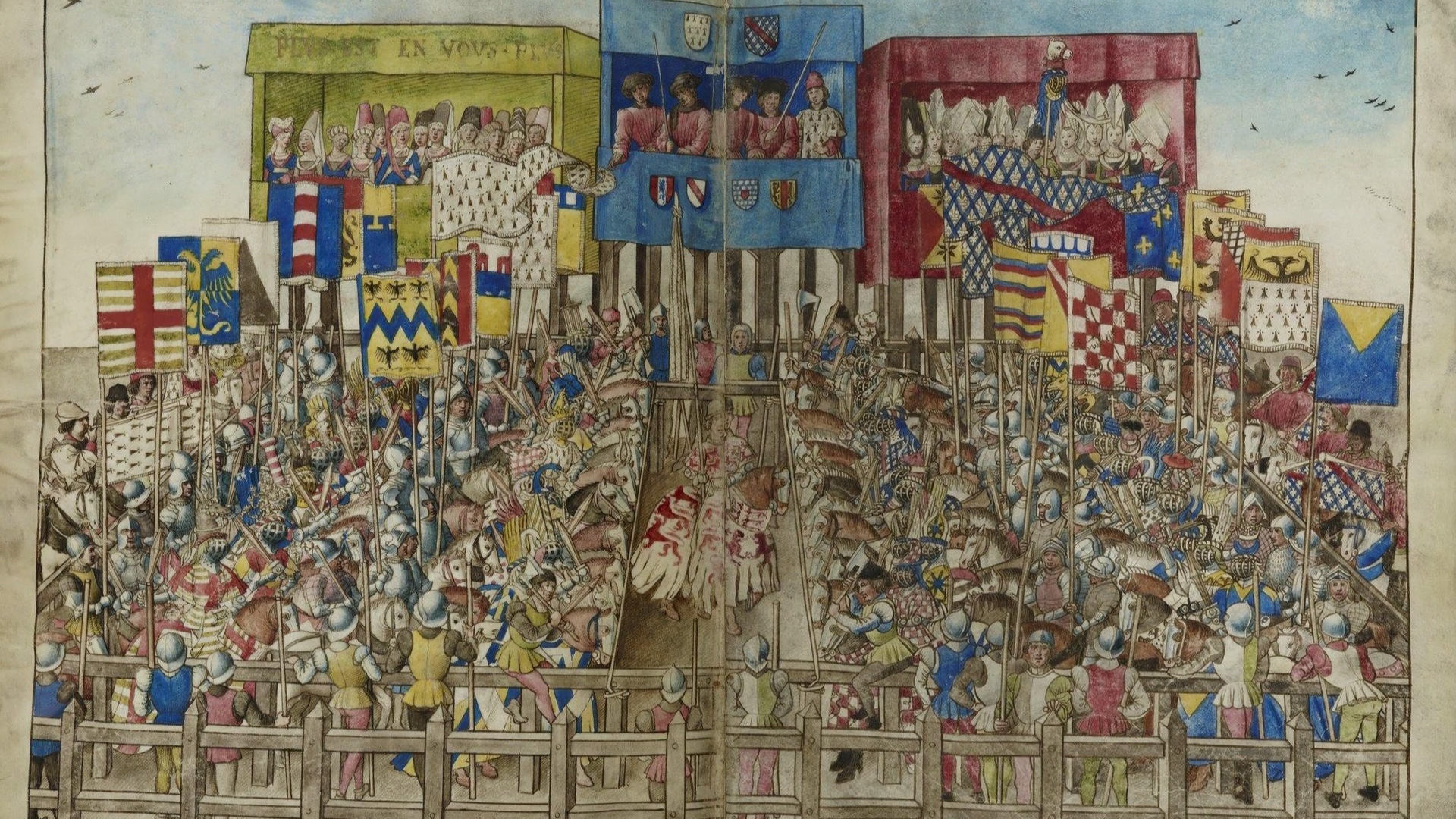

Early Tournaments

Small-scale tourneys did appear earlier, but the 1100s saw tournaments increase in popularity and scale, especially in what’s now north-east France. These early tournaments were far from the glitz and glamour of A Knight's Tale 200 years later, and while there was an element of flair and pagentry, they were very much war games, played out across large sections of land that could be 50 km (30 miles) wide, with hundreds of knights in opposing teams, which allowed them to practice tactics and gain experience that could actually be useful in war. Interestingly, the teams in these war games naturally divided themselves into factions that might otherwise be fighting wars – so you could easily face down men in a tourney that you would later fight for real.

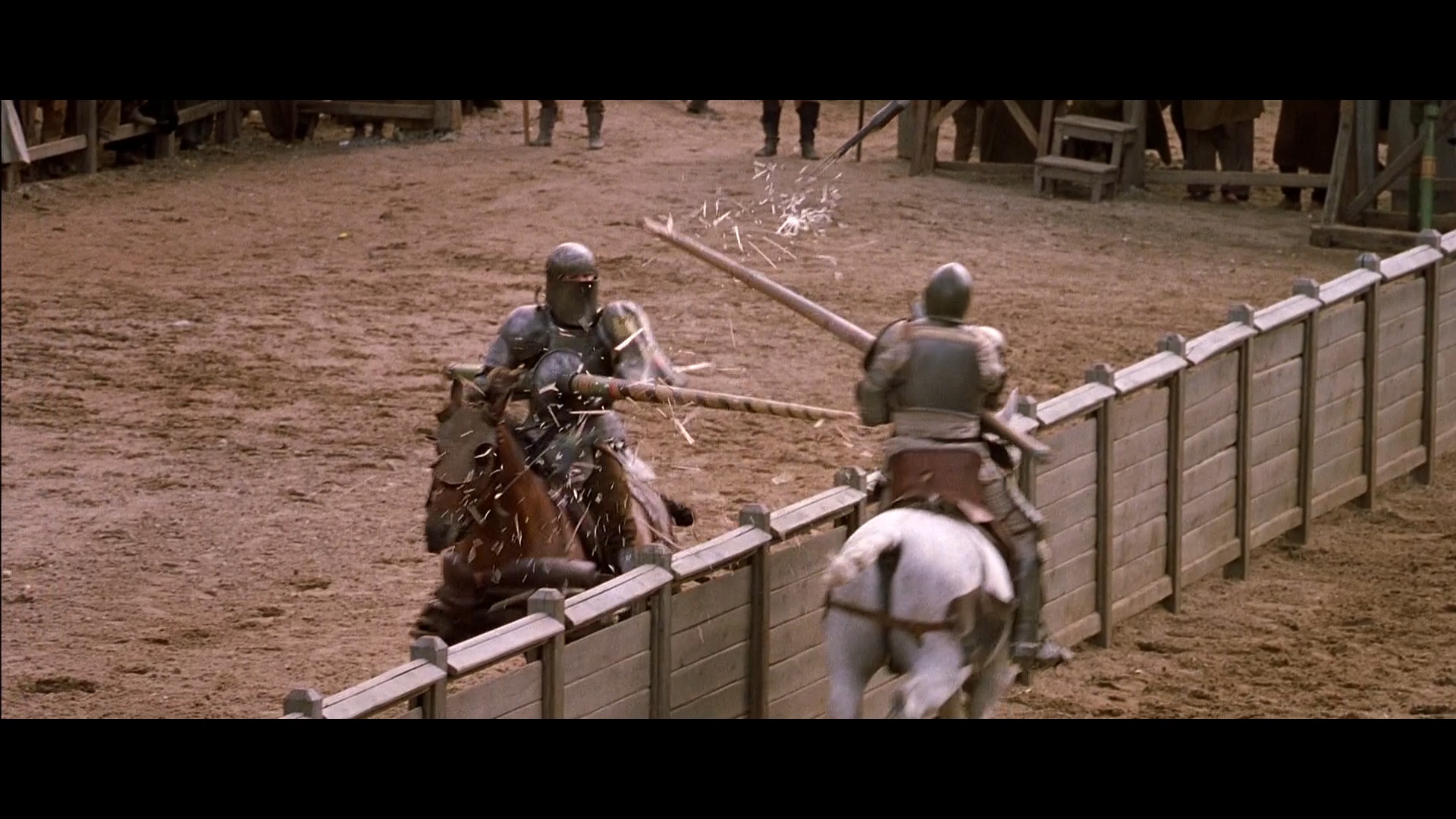

Knights would arrive the day before the tournament and there might have been some one-on-one jousts or practice matches that evening, but the melee was undoubtedly the main event. Mid-morning, the retinues would gather at two opposing “lists”; which were fences or pens, set up for the occasion. A horn blast would then set things off and the two sides would crash together. To quote from Thomas Asbridge’s The Greatest Knight:

Tournaments were not without risk, both physically and monetarily. We have no indication that these early tournaments used blunted weapons - instead armour was relied upon to protect the knights, and while the armour was good, accidents did happen. Asbridge’s book is about William Marshal and even though he lived centuries before A Knight's Tale, there’s an anecdote that matches up almost perfectly with William Thather’s first tilt: In 1170 after a grand melé there was great debate among the participants about who should get the MVP award. They decided on William Marshal but he was nowhere to be seen – eventually they found him in a forge with his head on an anvil and a blacksmith trying to pry his smashed and battered helmet off his head with an array of hammers, wrenches and pincers.

While William Marshal was commended as the best knight that day, there were few formal prizes to compete for in these early tournaments. Instead you mostly gained financial reward through the capture of opossing knights in the melee, for which you would get ransom money, much like in an actual war. Along with the great expense of participating in the first place, this meant that knights and their families could be ruined by debts incurred through repeated defeats.

Just like in A Knight's Tale, showing off and gaining a reputation was a big part of why you participated in tournaments - but while these war-games were better than the jousts of A Knight's Tale for learning what battles were like, they were much worse for spectators; usually there was a distinct lack of fair maidens to impress because this wasn’t yet a spectator sport. While there could be plenty of common people around at the large fairs that sprang up at tournament grounds, these were merchants, armourers and entertainers that came for trade, not to paint their faces and wave flags. And regardless, those weren’t the people you wanted to impress – you were instead trying to get the attention of your co-competitors. After all, their esteem would be much more valuable than that of any “plebs” who might be watching.

Now, the church did try to stamp out tournaments, even going so far as to forbid those who died in tournaments from being buried on consecrated ground, effectively condemning them to hell, but they only increased in popularity. By the 1160s, events were paused for lent but otherwise occurred regularly throughout the year, sometimes as often as every two weeks. The well-known contests soon formed into a schedule and a circuit of sorts and, over time, the games got more complex.

From Mêlée to Joust

In England, tournaments were banned until Richard I created a licensing system in 1194 which allowed for official, sanctioned tournaments. this was done in part because English knights kept going to France and getting their asses kicked, so no foreign knights were allowed in these English tournaments. you also had to pay a licensing fee, both to hold the tournament and to participate, and they could only be held between specific towns – none of which were in the west or north, where the king’s control was relatively weak. this points to another danger of tournaments: a gathering of armed men is inherently political and tournaments were a good place to conspire against the king, soft launch a rebellion, or try to make political assassinations look like accidents.

Tournaments could also be a dangerous distraction; in the 1290s, England had multiple wars going and the king – otherwise fond of tournaments – had to imprison large numbers of knights for leaving his army and going back to England to attend tournaments during lulls in the fighting. For these reasons, kings banned and unbanned tournaments on and off over the decades and centuries, but, in general, tournaments were more useful than harmful to savvy rulers; they were great places to demonstrate power, build alliances and strengthen feudal bonds — and to build the national identity and pride that would make it easier for kings to get their wars funded. Tournaments therefore came to be held in connection with celebrations of all sorts, from coronations and royal christenings to diplomatic meetings and, above all, weddings.

The church ban was even lifted in 1316 when the French royal family put pressure on their newly minted Avignon pope. The church had tried to scare people off with ghost stories, and tales of knights punished in hell with their armour nailed to their flesh but, in the end, tournaments proved useful to the church as well, as they were great places to recruit knights for their holy wars.

Note that throughout this essay, I’m using the word “tournament” to refer to the whole event – as most people would today – but the word originally referred just to the free-for-all melees. These mock battles were difficult for spectators to follow, even with the addition of easily recognisable armorial bearings and crests, and this is probably part of why jousts — like we see in A Knight's Tale — grew increasingly popular over time and supplanted the melee as the “main event”.

More spectators also meant more risk of injury to onlookers and while some towns simply let knights go at it in their main squares, watching from the windows and roofs above, using fenced in areas became the norm. Often this would be a double fence, with foot soldiers and squires stationed between the two barriers, ready to subdue the crowd or assist their masters, as needed. Around the year 1400 they added a central barrier to separate the combatants, and sometimes there would be additional railings on the “outside” of each knight, to ensure a satisfying collision.

Now, if you were a knight bored with these new jousts and hungering for a taste of old-school combat, you didn’t have to look far — the 100 Years War and wars in Scotland provided a great outlet for aggression and, surprisingly, I’m not talking about battles, I’m talking about “jousts of war”. These were tournaments of sorts but fought between knights on opposing sides during an actual conflict. Most common were single combats with no significant injuries, fought during sieges to entertain both sides, but we have plenty of records of jousts of war that got a bit more out of hand. In 1341, twenty English knights challenged twenty Scottish knights to three days of combat, during which three participants died and many more were injured — even so, heralds awarded prizes to the best performers on each side. Ten years later we saw the famed Combat of the 30, which inspired similar events in Gascony the following year (with twenty French knights fighting mortal combat against twenty Gascon knights) and thirty years later at Rennes (with fifteen English knights facing fifteen French).

Tournaments were popular across much of Europe and its not surprising that different regional styles developed. In the Low Countries, tournaments were held as part of town festivals, special events paid by the city where burghers had the right to carry arms and crests and they jousted alongside the nobility as equals. Perhaps this was in part permitted because these were local affairs where foreign participants were extremely rare. In contrast, Germany in the 1400s had the strictest entry requirements for their melees, only allowing participants who could give evidence of noble birth on both sides of the family for four generations. Interestingly this restriction only applied to the melee; it seems that anyone who could acquire a horse and suit of armour was allowed to joust.

In A Knight's Tale, Adhemar the Antagonist hides a pointed tip in order to injure William. In reality, knights could often choose whether they wanted to jousts with “lances of peace” or “lances of war”. As jousts grew in popularity, more specialised armour and protection was introduced, including a rounded shield with a bite taken out of it to allow easier aiming of the lance. This shield would be shown by a knight awaiting a challenge, often alongside a triangular shield of war, and a challenger would strike the shield of peace or the shield of war to indicate whether they wanted to use blunted or sharp weapons.

Shrovetide, the festival that came before lent, was the most common time to hold tournaments, though Christmas and Easter were other popular dates. Heralds would often be sent out to publicise an upcoming tournament, and those wishing to take part would arrive days before the event, displaying their shields at the windows of their inns. Often events started on Monday or Tuesday, allowing you to fit in three days of jousting before Friday, the day of fast. These events could get quite massive; the Black Prince hosted a tournament celebrating the birth of his eldest son at which there were 154 lords, 706 knights and, supposedly, 18,000 horses present.

Speaking of the Black Prince, it’s funny that in A Knight's Tale he hides his identity to compete because princes and kings often proudly participated in the fighting, though sometimes in more friendly versions of the tournament (called behourd) where they might use boiled leather armour and whalebone swords. where there are records of kings and princes participating in disguise it’s usually part of the pageantry rather than a necessity to be able to compete. The black prince’s parents were both tournament enthusiasts, and his mother’s presence at events encouraged other noble women to attend. Richard Barber and Juliet Barker wrote this in their book “Tournaments”:

For example, after quarrelling with the church, one of the king’s household knights dressed as the pope during a tournament, with twelve companions playing the role of cardinals. And at a later Cheapside tournament, seven knights jousted dressed as the Seven Deadly Sins, much to the horror and titillation of the spectators. To celebrate John of Gaunt’s marriage, the king and his sons, including the Black Prince competed against challengers dressed as the mayor and aldermen of London.

But fancy dress was only the beginning; in the late 1300s, theatres started using scenery and set pieces as major elements in their productions, and tournaments did the same. Such elements weren’t new — as far back as 1267, a wood of trees was built outside a German town, with one tree bearing gold and silver leaves - anyone who broke a spear in a joust was awarded a silver leaf, and anyone who unhorsed their opponent was awarded one of gold, but after the 1300s, these sets grew more elaborate. In 1428, a fortress with a high tower was built in the main square of a Spanish town, with a belfry, a gilded gryphon and four great towers surrounding it, each tower housing a lady in fine dress. In 1446 in France, another wooden castle was built and the jousting opened with a procession that included two Turks dressed in white leading real lions.

That particular event was of a sort that was becoming increasingly popular; a Pas d’armes, where one or several knights would pick a location, often a bridge or city gate, and proclaim that any knight who wished to pass would have to fight, or face disgrace. Often the knights stayed in these locations for months, setting a goal of breaking a certain number of lances in a certain number of days. If this sounds like something out of a fairytale romance, it’s because that’s because that’s where they got the idea. The tournament had a symbiotic relationship with courtly romances and fantastical Arthurian tales; and over time, it transformed into a stage to play out such storylines. if you’ve ever been to modern-day joust you may have noticed similarities with “pro wrestling”; while outcomes might or might not be predetermined, much current-day jousting has a manufactured drama and roleplaying that is not unique to the modern day; far from it, medieval knights would host “Round Tables,” where they would emulate Arthurian tales, dressing up as the knights of the round table and fighting jousts in character.

This increased pageantry, with jousters wearing 20 pounds of pearls, and using spring-loaded shields that flew apart when struck in the right spot, would spell the end of tournaments as we imagine them. In 1559, King Henri II of France died from a splinter that went through his visor, and that was more or less the end of monarchs participating in serious jousts. in the centuries that followed A Knight's Tale, the festivals surrounding jousts became more important than the actual fighting, which was reduced to an equestrian ballet with pre-determined movements and outcomes. As Francis Bacon wrote about tourneys in the 1600s:

![“[For jousts and tourneys and barriers,] the glories of them are chiefly in the chariots, wherein the challengers make their entry, especially if they be drawn with strange beasts, as lions, bears, camels and the like; or in the devices of their entrance; or in the bravery of their liveries; or in the goodly furniture of their horses, and armour.” “[For jousts and tourneys and barriers,] the glories of them are chiefly in the chariots, wherein the challengers make their entry, especially if they be drawn with strange beasts, as lions, bears, camels and the like; or in the devices of their entrance; or in the bravery of their liveries; or in the goodly furniture of their horses, and armour.”](https://awesomepedia.org/video/the-real-history-of-a-knights-tale/images/10-bacon-1.jpg)

Tournaments, once a proving ground for warriors, had transformed into a dramatic display and, in the 1700s, this too would largely come to be replaced by military parades, as a much more straight-forward way for rulers to display their power. But you cannot fully understand tournaments without learning about some of the key players that contributed to their development — one of whom bears a name you might be familiar with.

Ulrich von Lichtenstein

In the film, William Thatcher was a real person who invented a fictional Ulrich von Lichtenstein. In reality, Ulrich von Lichtenstein was a real person – who also invented a fictional Ulrich von Lichtenstein. He was born a century before the film takes place, and he was from what’s now Austria rather than Gelderland. Ulrich is a clever choice for William’s alter ego because the real Ulrich was an extraordinary jouster and a well-known poet.

He wrote a highly fictionalised book of his own adventures, titled Service of Ladies, which largely concerns his pursuit of a married woman, just as the conventions of courtly love dictate. At a young age, he became a page to this lady of a higher status and he grew enamoured with her, conducting little acts of boyish love such as picking her flowers and drinking the water she washed her hands in. You know, normal stuff! He was later knighted and spent years trying to convince the lady in question of his devotion in increasingly silly ways, all while she treated him with seeming contempt. When he heard that she’d rejected him for his “disfigured mouth”, he underwent plastic surgery immediately, not realising that she was probably commenting metaphorically on his imprudent way of speaking, rather than about his mouth’s physical shape. This type of comedy infuses the whole tale – at one of his many jousts in her honour, he injures a finger and she is impressed that he’s lost a finger in her service, but she grows disappointed and accuses him of lying when a doctor helps him fix the problem. What else could Ulrich do but chop off his finger and send it to her as a symbol of his devotion? And this is all before his most over-the-top act of “service”.

In the winter of 1226-27 he travelled in secret to Venice where he hired servants who did not know his identity and gathered a great quantity of women’s clothes. He sent a herald ahead of him to let all knights know that Queen Venus, the goddess of love, would travel through their lands to teach them the ways of love, gifting every knight who broke a lance with her a golden ring to give to their beloved. Dressed fabulously in white women’s clothes and with two waist-length braids bound with pearls, he set off with his retinue and caused a great sensation wherever he went, and he broke 307 lances on his journey to Bohemia without ever being unhorsed himself. After this, the lady granted him a meeting, asking him to disguise himself as a leper and mingle with those seeking alms outside her castle, supposedly to allow a surreptitious entry but in actuality more likely designed to humiliate him further. When he was eventually allowed entry to her chamber it was via a loop of bedding lowered from her window, by which he would be hoisted up. Three times the lady dumped him on the ground before he sent his squire up to help with the hoisting. Even after all this, he still didn’t get lucky, and his passion finally withered when the lady committed some awful act, which Ulrich, the author of this story, was too chivalrous to reveal. Given the horrible acts that he did include, one might presume that this act was very awful indeed.

Of course, this story is as real as A Knight's Tale. When I first read about it, I thought it sounded like Ulrich, the author, was slighted in his own mind by some woman and decided to write a series of poems about what a horrible bitch she was and about how he’s the best dude ever. (A tradition male writers have proudly kept up in the intervening centuries.) But to be fair, there’s a bit more to it than that. In the second part of his novel, Ulrich seeks the affection of another lady and completes a similar journey, this time dressing up as King Arthur and inviting knights he broke lances with to his round table. The whole book, in fact, uses the form of an Arthurian romance with events and motifs borrowed from other stories, such as Tristan meeting the queen Isolde disguised as a leper. But Ulrich turns everything on its head, switching up the gender dynamics of these stories for comedic effect – while his first love is painted as contemptuous towards Ulrich, he, ultimately, is the fool of the story, a caricature so committed to courtly love and chivalric ideals that he goes to absurd lengths to prove his love, allowing the author to poke fun at these conventions.

The real Ulrich died in 1275 and while he appears in records of the time, we mostly know him through his writing. Over the years there’s been much speculation about which of his described events might have actually taken place (spoiler alert: probably none of them) and about potential hidden political meanings in the text. But one thing is for certain - given his habit of playing with norms and tropes and the fact that Ulrich, the character, was one driven to overcome insurmountable odds with pig-headed stubbornness and excellent jousting, they truly could not have picked a better name for William Thatcher.

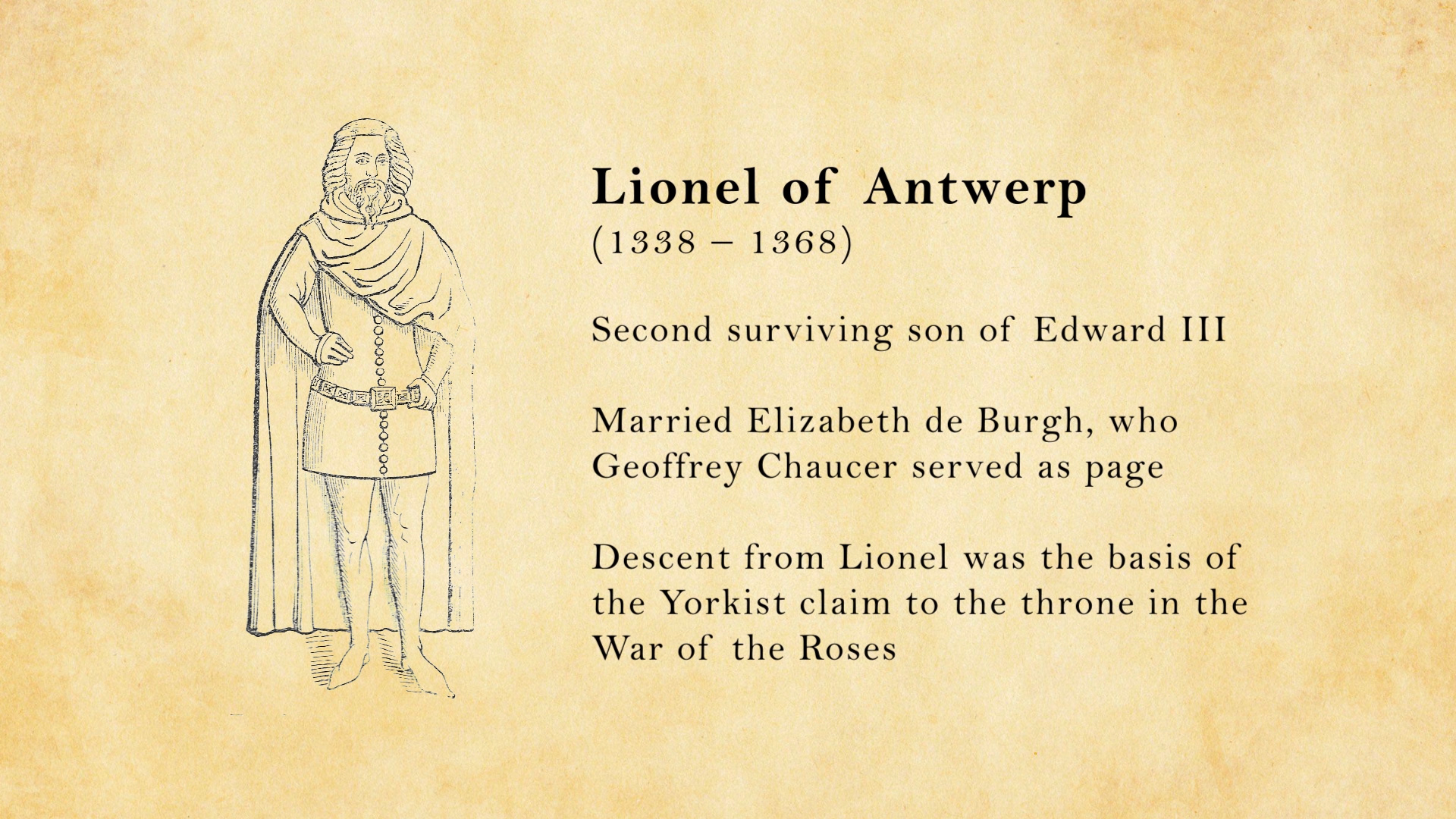

The Black Prince

The Black Prince, born in 1330 to Edward III and Philippa of Heinolt, was heir apparent to the throne, Duke of Cornwall, Earl of Chester, the Prince of Wales & Aquitaine and – most importantly – the guy who knights Heath Ledger at the end. He was the eldest of 13 children and though he never became king, he was father to King Richard II. He seems to have been tall, well-built and handsome, and just like in A Knight's Tale, he was fond of tournaments and jousting.

You might be wondering why he was called the Black Prince? Well, he wasn’t actually called that in his lifetime, it was 150 years later that we first saw that moniker written down, and we don’t really know where it came from. Some think it was the colour his armour and shield – in Victorian England they went so far as to paint his monument in Canterbury Cathedral black to fit this theory. Others think it was a French nickname based on his grim reputation in France, which was well deserved.

He would have been campaigning in France with his father from the age of 13; at the Battle of Crécy at age 16 he’s said to have asked the king for reserves and his father responded “let the boy win his spurs”. This probably didn’t happen but you can see why the story is told; it’s a compelling anecdote showing how Edward’s upbringing was one of war. After that battle he honoured the King of Bohemia, who died fighting spectacularly on the French side, by adopting his ostrich feather badge as his personal insignia, with the slogan Ich dien; I serve.

(Quick aside – you know how in films you always see kings rushing headfirst into battle? That’s often not the case but 50-year old John of Bohemia was at least half blind and he was still in the centre of all the fighting because he had his men lead his horse there so he could get in on the action!)

The Black Prince married Joan of Kent, which would have been an unusual match. Given the need to forge alliances with other crowns, no heir to the English throne had taken an English bride since the Norman conquest and, on top of that, Joan was in her thirties and had already had five children from her previous husband. They were also cousins, which wasn’t too unusual though it meant the king had to petition the pope to get permission for them to marry. Joan had an eventful past at that stage; around the age of 12/13 she was married to 26-year-old Sir Thomas Holland and then, when Sir Thomas went off to fight in the war, her family married her to another man, William Montagu, who was, at least, around her same age. It seems the original marriage was kept secret and Sir Thomas made no mention of it, until a few years later when he’d made a name for himself, fighting in France. At that point he brought the matter to the papal court and got his wife back in 1349. Thomas Holland died in 1360, and within a year she was married to the Black Prince. Shortly after their marriage, the two of them packed up in England and headed to Aquitaine which was Prince Edward’s to rule after the Treaty of Brétigny.

It seems fair to say that the Black Prince was better at war and partying than intrigue and administration. The Battle of Poitiers was his greatest military achievement, but there were many others. He was generous to those who served him well – in his early years he took little profit from ransoms, distributing rewards to his companions instead, and in his great hall in Bordeaux he fed over 80 knights and 300 squires every day. He had a massive retinue, loved banquets, hunting and tournaments and, to be fair, this was a good way to maintain the allegiance of those who already liked you. But there were plenty of people in Aquitaine who didn’t like him. He was spending more than he had and it fell on the local population to make up the difference via taxes. While the region had been held by England for a good while, it was still very much on the continent, and they recently had the French crown as their ultimate overlord, so they weren’t too keen on the Black Prince’s perceived arrogance, extravagance, and favour for his own favourites rather than the local lords - all of which led them to turn back towards France.

The war with France never really ended; officially there might have been peace but the Black Prince was down in Spain fighting in a proxy conflict for years. There he grew ill with dysentery, as did many of his men, and his health never recovered. After his return to Aquitaine, tensions only escalated with the local lords, eventually leading to war. King Charles of France was shrewdly negotiating towns and nobles back into the French fold, mostly by promising reduced taxes, and this was a maddening thing for the young warrior prince to watch from his sickbed. One town he might reasonably have considered safe was Limoges, where the bishop was a personal friend and godfather to the Black Prince’s son. However, in 1370, the town swapped allegiance back to France, and the Black Prince became incensed and determined to make an example.

Commanding a siege of the town from a litter, he had miners tunnel in and after a month they were able to collapse sections of the wall. Men-at-arms poured in, blocked the city’s exists and the prince ordered a massacre of the population. A massacre of civilians is always a dick move but it’s even worse because bear in mind that the nobles, the ones who decided to swap allegiances, would have been kept alive for ransom, and the bishop was handed back to the (French) pope. Meanwhile something like 3,000 common men, women and children were dragged out of their houses and had their throats cut. What a cool guy, this Black Prince fellow! (Note that these casualty numbers are disputed by Black Prince fanboys who claim it’s closer to 300.)

Besides being a horrible atrocity, the massacre at Limoges didn’t fill its intended aim. Sure, in the short run it might have stopped some towns from switching over to France, but in the long run it only increased the hatred of the English across the region which, within 50 years, would bring Joan of Arc to Orléans and spell the end of English dominion on the continent. As for the Black Prince, his illness was only getting worse and to top it off, his eldest son died from the plague around this time. The Black Prince handed over Aquitaine to his brother, John of Gaunt, and returned to England where he spent six more years of ill health before passing away in 1376 at the age of 45. His father died just one year later, and the throne passed to the Black Prince’s son Richard, who was then ten years old.

Adhemar & The Free Companies

In A Knight's Tale, another person running around France causing havoc was Count Adhemar. Unlike the Black Prince, Ademar wasn’t real – but he does represent an archetype that’s worth exploring. He’s introduced in the film as “Adhemar, Count of Anjou, son of Philippe de Vitry, son of Gilles, defender of his enormous manhood”. Those titles are a real hodgepodge, but Philippe de Vitry was an actual person, a French composer and bishop who lived at an appropriate time to be Adhemar’s father (31 October 1291 – 9 June 1361). Some sources claim Philippe de Vitry was born in the Champagne region, which kind of makes sense of the “chivalry and champagne” line. Philippe de Vitry was in the court of several French kings, starting with the one whose death sparked the 100 Years War. I can’t find a reference to him ever having any children, let alone a leader of the free companies, so we might assume that this name was picked more or less at random, though Philippe’s eminence makes him an appropriate parent for Adhemar.

Adhemar is described as the count of Anjou, one of the areas disputed during the 100 Years War, though held by the French crown even after the treaty of Brétigny. The actual count of Anjou was Louis, a son of the French king who escaped capture at the Battle of Poitiers. He was one of the hostages sent over to England to secure his father release while France tried to come up with the king’s ransom. Since the country was economically devastated, they had difficulty coming up with that ransom, meaning Louis was stuck in England much longer than he expected, and he decided to escape back to France, which his father the king disapproved of so much that he voluntarily returned into comfortable English captivity himself. Now, did you hear me say that France was economically devastated? Well, that wasn’t just the work of the Black Prince. It also had a lot to do with the Free Companies.

The Free Companies are hard to describe; they’re outlaws who became disciplined mercenaries, they’re English but they’re also French, and honestly, they’re from all over. The main thing that these men had in common was that they could fight and that they saw the appeal of riches and plunder. As I’ve described, violent horse raids across the land were an essential part of warfare at this time, and the men who practiced it under the Black Prince became very good at it. Then, after the Battle of Poitiers, their services in this area were no longer required and when they were released, many gathered around captains in groups of twenty to fifty and in the years that followed these groups would swell, merge and get organised. After all, the French king was in captivity and there were still riches to be reaped from his land.